The Woman’s Headcovering

by Michael Marlowe, October 2008

I Corinthians 11:2-16.

2 Now I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions even as I delivered them to you.

3 But I want you to understand that the head of every man is Christ, the head of the woman is the man, and the head of Christ is God.

4 Every man praying or prophesying with anything down over his head dishonors his head,

5 but every woman praying or prophesying with her head uncovered dishonors her head—it is the same as if her head were shaven.

6 For if a woman will not be covered, then let her be shorn! But since it is disgraceful for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered.

7 For indeed a man ought not to cover his head, being the image and glory of God; but woman is the glory of man.

8 For man was not made from woman, but woman from man.

9 Neither was man created for woman, but woman for man.

10 For this reason the woman should have authority on her head, because of the angels.

11 In any case, woman is not independent of man, nor man of woman, in the Lord;

12 for as woman is [created] from man, so man is now [born] through woman. And all things are from God.

13 Judge for yourselves: is it proper for a woman to pray to God with her head uncovered?

14 Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair it is a disgrace for him,

15 but if a woman has long hair, it is her glory? For her hair is given to her for a covering.

16 But if anyone is inclined to be contentious, we have no such practice, nor do the churches of God.

2 Now I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions even as I delivered them to you.

3 But I want you to understand that the head of every man is Christ, the head of the woman is the man, and the head of Christ is God.

4 Every man praying or prophesying with anything down over his head dishonors his head,

5 but every woman praying or prophesying with her head uncovered dishonors her head—it is the same as if her head were shaven.

6 For if a woman will not be covered, then let her be shorn! But since it is disgraceful for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered.

7 For indeed a man ought not to cover his head, being the image and glory of God; but woman is the glory of man.

8 For man was not made from woman, but woman from man.

9 Neither was man created for woman, but woman for man.

10 For this reason the woman should have authority on her head, because of the angels.

11 In any case, woman is not independent of man, nor man of woman, in the Lord;

12 for as woman is [created] from man, so man is now [born] through woman. And all things are from God.

13 Judge for yourselves: is it proper for a woman to pray to God with her head uncovered?

14 Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair it is a disgrace for him,

15 but if a woman has long hair, it is her glory? For her hair is given to her for a covering.

16 But if anyone is inclined to be contentious, we have no such practice, nor do the churches of God.

Greek Text

2 Ἐπαινῶ δὲ ὑμᾶς ὅτι πάντα μου μέμνησθε καὶ, καθὼς παρέδωκα ὑμῖν, τὰς παραδόσεις κατέχετε.

3 Θέλω δὲ ὑμᾶς εἰδέναι ὅτι παντὸς ἀνδρὸς ἡ κεφαλὴ ὁ Χριστός ἐστιν, κεφαλὴ δὲ γυναικὸς ὁ ἀνήρ, κεφαλὴ δὲ τοῦ Χριστοῦ ὁ θεός.

4 πᾶς ἀνὴρ προσευχόμενος ἢ προφητεύων κατὰ κεφαλῆς ἔχων καταισχύνει τὴν κεφαλὴν αὐτοῦ.

5 πᾶσα δὲ γυνὴ προσευχομένη ἢ προφητεύουσα ἀκατακαλύπτῳ τῇ κεφαλῇ καταισχύνει τὴν κεφαλὴν αὐτῆς· ἓν γάρ ἐστιν καὶ τὸ αὐτὸ τῇ ἐξυρημένῃ.

6 εἰ γὰρ οὐ κατακαλύπτεται γυνή, καὶ κειράσθω· εἰ δὲ αἰσχρὸν γυναικὶ τὸ κείρασθαι ἢ ξυρᾶσθαι, κατακαλυπτέσθω.

7 Ἀνὴρ μὲν γὰρ οὐκ ὀφείλει κατακαλύπτεσθαι τὴν κεφαλήν, εἰκὼν καὶ δόξα θεοῦ ὑπάρχων· ἡ γυνὴ δὲ δόξα ἀνδρός ἐστιν.

8 οὐ γάρ ἐστιν ἀνὴρ ἐκ γυναικός ἀλλὰ γυνὴ ἐξ ἀνδρός·

9 καὶ γὰρ οὐκ ἐκτίσθη ἀνὴρ διὰ τὴν γυναῖκα ἀλλὰ γυνὴ διὰ τὸν ἄνδρα.

10 διὰ τοῦτο ὀφείλει ἡ γυνὴ ἐξουσίαν ἔχειν ἐπὶ τῆς κεφαλῆς διὰ τοὺς ἀγγέλους.

11 πλὴν οὔτε γυνὴ χωρὶς ἀνδρὸς οὔτε ἀνὴρ χωρὶς γυναικὸς ἐν κυρίῳ·

12 ὥσπερ γὰρ ἡ γυνὴ ἐκ τοῦ ἀνδρός, οὕτως καὶ ὁ ἀνὴρ διὰ τῆς γυναικός· τὰ δὲ πάντα ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ.

13 Ἐν ὑμῖν αὐτοῖς κρίνατε· πρέπον ἐστὶν γυναῖκα ἀκατακάλυπτον τῷ θεῷ προσεύχεσθαι;

14 οὐδὲ ἡ φύσις αὐτὴ διδάσκει ὑμᾶς ὅτι ἀνὴρ μὲν ἐὰν κομᾷ ἀτιμία αὐτῷ ἐστιν,

15 γυνὴ δὲ ἐὰν κομᾷ δόξα αὐτῇ ἐστιν; ὅτι ἡ κόμη ἀντὶ περιβολαίου δέδοται [αὐτῇ].

16 Εἰ δέ τις δοκεῖ φιλόνεικος εἶναι, ἡμεῖς τοιαύτην συνήθειαν οὐκ ἔχομεν οὐδὲ αἱ ἐκκλησίαι τοῦ θεοῦ.

Text-critical notes

In verse 2 the Latin versions and the later Greek manuscripts read αδελφοι “brethren” after Ἐπαινῶ δὲ ὑμᾶς “I commend you.” But the word is absent from the early Greek manuscripts (Papyrus 46, A, B, C, א) and the Coptic versions, and so it is omitted by all modern editors. The word was probably added by scribes because they perceived that this was the beginning of a new section, and it seemed natural to have the word here, as in 10:1 and 12:1. It may be that Paul omitted “brethren” deliberately because the headcovering tradtion has more to do with the sisters.

In verse 11 the Vulgate, the Peshitta, and a few of the later Greek manuscripts (followed by the Textus Receptus editions) transpose the two clauses to read “the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man.” But all the earlier Greek manuscripts have “the woman” first. Probably the original order of the clauses was accidentally reversed by scribes who were used to Paul’s usual pattern of mentioning the man first in statements that contrast men and women (see verses 7, 8, and 9).

In verse 15 there is some reason to think that the pronoun αὐτῇ “to her” at the end of the verse is not original. It is omitted by Papyrus 46, D, F, G, and also by the majority of later Greek manuscripts. In C the pronoun comes before δέδοται rather than after it. The word may have been added by scribes to complete the sense, or simply by repetition of the αὐτῇ in the preceding clause. But it has good support in A, B, א, and the Latin and Syriac versions.

Commentary

2 Now I commend you because you remember me in everything and maintain the traditions even as I delivered them to you.

The Apostle here indicates that the following instructions pertain to the παραδόσεις, “traditions” (lit. “things delivered or passed on”) which he has previously conveyed to the churches under his care. The verb translated “delivered” here is a form of παραδιδωμι, the verbal cognate of the noun παραδοσις. In religious contexts these words were used of anything handed down to disciples, whether in the form of doctrine, narratives, or regulations. The KJV translates the noun “ordinances” here, with an eye to the regulations discussed in the chapter, and the NIV has “teachings,” but neither of these give the true sense of the word. Paul could have used a word like δικαιωματα “ordinances” or διδασκαλια “teachings” if he had wanted to refer specifically to either ordinances or teachings. Instead, he uses παραδόσεις, along with its cognate verb, because he is emphasizing the fact that he is now speaking of things handed down as traditions.

Paul’s conception of the purpose of “tradition” may be seen from other uses of these words in his epistles. In this same chapter, verse 23, he uses the verb again at the beginning of his discussion of the Lord’s Supper: “For I received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you.” In 15:3, he uses it at the beginning of his discussion of the Resurrection: “For I delivered unto you first of all that which also I received.” In 2 Thessalonians 2:15 the noun is used in Paul’s exortation, “stand fast, and hold the traditions which ye were taught, whether by word, or by epistle of ours.” From these examples, we see that Paul invokes “tradition” as something that will keep his disciples on the right track in the midst of spiritually dangerous developments. The chaotic situation in Corinth, in particular, where meetings had come to be dominated by persons claiming extraordinary spiritual gifts, called for this emphasis. But Paul opens the subject in a conciliatory manner, commending them for their general willingness to adhere to the traditions he has given them. (1)

The subject of the following verses may seem trivial to modern readers. On the surface, Paul is addressing a problem arising from some irregularities or objections connected with women’s headcoverings. This may have seemed unimportant to some ancient readers as well. But Paul uses the occasion to make some important statements about men and women that go well beyond the issue at hand.

3 But I want you to understand that the head of every man is Christ, the head of the woman is the man, and the head of Christ is God.

Here he states the general thesis which governs the entire discussion that follows. He indicates that there is a divinely ordained hierarchy, in which men are directly under Christ as their “head” while women are under the headship of man. Christ is directly under the head of God the Father in this grand scheme of things. A similar hierarchical conception was expressed by Paul earlier in the epistle, in 3:21-23, where the arrangement is of teachers under the church, which is under Christ, who is under God. There the relationship is expressed in terms of ownership. The point concerning Christ being under God is also repeated in 15:28, where it is expressed in terms of subjection. Paul mentions it here, in the context of his discussion of the relationship between men and women, so as to impress upon the Corinthians how important the “chain of being” principle of hierarchy is in spiritual matters, and in the very constitution of the universe. And perhaps he mentions the subordination of Christ in particular to suggest the teaching we have in the second chapter of the Epistle to the Philippians:

Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped.

The subordination of the woman to man is no more done away with in Christ than is the subordination of men to Christ. Christ himself is functionally subordinate to God the Father, and did not “seek equality” with God. Though he is the “radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and upholds the universe by the word of his power” (Hebrews 1:3) he also willingly fills his place in the divine economy. We will have reason to come back to this thought when Paul begins to speak of the “image and glory” of God in in verses 7 and 8 below.

It may be that Paul had information that certain women in Corinth were falling into extravagant notions of Christian liberty (the usual problem at Corinth — “all things are lawful to me”), and had cast off their headcoverings in some kind of demonstration of sexual equality. 14:34-35 gives us some reason to think that egalitarian tendencies had created problems at Corinth. If this was the case, then Paul’s words here go straight to the root of the problem. (2)

Some recent commentators have suggested that the Greek words for “man” and “woman” used here (ἀνήρ and γυνή) may be understood in the limited sense of “husband and wife,” but for several reasons it is better to understand the whole discussion as pertaining to the relationship between the sexes in general. Ordinarily a pronoun is used with the Greek words when they have the sense “husband” and “wife” (i.e. her man means her husband, and his woman means his wife), but there is no pronoun here. It is very unlikely that Paul is referring only to married men when he says “Every man praying or prophesying with anything down over his head dishonors his head” in verse 4, and if ἀνήρ does not mean “husband” there, we would not expect γυνή to mean “wife” in the following verse. We would expect the terms to be correlated in sense when they occur together — either “man and woman” or “husband and wife,” but not “man and wife” or “husband and woman.” Paul proceeds to make arguments based not upon the special circumstances of marriage but upon creation and the very nature of woman. The analogy he draws between the headcovering and the long hair of women (verses 6 and 15) would apply to all women. It does not make sense to limit the meaning of γυνή to “wife” in the phrase, “since it is disgraceful for a γυνή to be shorn or shaven” (verse 6), and so the conclusion, “let her be covered” cannot be restricted to married women either. In verse 12 the phrase ὁ ἀνὴρ διὰ τῆς γυναικός cannot mean “the husband is born through the wife.” It should also be kept in mind that in ancient Greek society, unmarried women were not independent, but remained under the authority of their fathers. Unmarried women did not live alone. In classical Athens the only independent women were the hetaerae — prostitutes of the upper class. (3) Even if it is felt that Paul must have in mind the marriage relationship here, it should be understood that this relationship is paradigmatic of the relationship of men to women generally (4)

4 Every man praying or prophesying with anything down over his head dishonors his head,

5 but every woman praying or prophesying with her head uncovered dishonors her head—it is the same as if her head were shaven.

The interpretation of this verse, and of the remainder of the passage, has varied widely among commentators because of their different ideas about Greek and Jewish customs of the time. I give an illustrated survey of the customs of Jews, Greeks, and Romans in the excursus on headcovering customs in the ancient world. To summarize the matter briefly here, I will only say that there is not enough evidence in ancient sources to conclude that Paul is advising conformity to Corinthian customs in this passage. On the contrary, ancient sources indicate that Greek women commonly participated in religious ceremonies without headcoverings. Nor does it seem that he is advising conformity to Jewish customs, in which women hid their faces in public. The use of headcoverings by women in daily life was common enough throughout the ancient world that we would expect Paul to make his meaning clear if he were requiring not only this but also the face-veiling. We would expect him to use a word or expression for the face-covering or veil (καλυμμα), at least, but that is not the case here. Instead, Paul uses only a very general word for “covered,” κατακαλυπτω, and he does not mention the “face” (τὸ πρόσωπον), only the “head.” (5) He is certainly not advising conformity to Roman customs of his day, in which male priests normally covered their heads for ceremonies. But clearly he is urging the Corinthians to observe an established custom of the Church. This custom was established by Paul in his Gentile congregations, probably after the example of the Jewish custom, but it was somewhat more liberal in its requirements than the stricter Jewish custom. Christian women were expected to cover their heads—but not their faces—in religious exercises, and especially in meetings. It is very doubtful that in this matter Paul would have cared much about what pagan women happened to be wearing on the streets of Corinth at the time.

It is necessary to emphasize here that in ancient cultures the symbolic value of clothing was taken very seriously. This was true not only of pagan cultures and cults, but of Judaism and Christianity as well. Jesus and the apostles could take it for granted that their disciples appreciated the significance of clothing. In Matthew’s version of the parable of the wedding feast, there is a dramatic confrontation about proper attire when the King asks a certain man: “Friend, how did you get in here without a wedding garment?” (Matthew 22:12) A modern reader is likely to find it strange that such importance is placed upon clothing, but the original hearers of this parable would not be inclined to sympathize with the underdressed man. They would think, rather, that the man who would not dress properly showed contempt for the King and his son, and obviously did not belong there. Indeed the man in the parable could offer no excuse for his own behavior, for “he was speechless.”

Some recent commentators have made much of the word “prophesying” in verse 5 (which Paul simply repeats from the expression in verse 4), and have argued that the inclusion of this word here proves that Paul allowed women to prophesy or speak independently in the worship service. These scholars must then dispose of 14:34-35 (“let the women be silent ...”) and 1 Timothy 2:11-12 (“a woman should learn in silence”) in various improbable ways. But there is nothing in this passage which suggests that Paul is here giving instructions only for those who are speaking in the worship service. “Praying or prophesying” is simply Paul’s way of referring to the corporate spiritual exercises of the church when it is gathered, in which every member participates to some extent. He is not limiting the headcovering rule to individuals when they are actually speaking, so that a man who wanted to veil himself like a Roman priest for the meeting could do so if he never ventured to pray or prophesy independently, or that a woman who wanted to be bareheaded like a Greek priestess would only have to put on her headcovering if and when she ventured to pray or prophesy in the worship service. That is not the idea here at all. The idea is that the women should wear headcoverings when the church is gathered for worship, instruction or prayer. We may assume that the Corinthians gathered for prayer at various times, in addition to gathering for worship on the Lord’s day, and that some meetings were less formal than others. The passage before us does not focus on the question of whether or not women should be speaking independently in the worship service conducted on Sunday. For a full discussion of this question see the excursus on 1 Corinthians 11:5.

The word προφητεία “prophecy” in the New Testament refers to any utterance prompted by the Spirit of God or any utterance which is presented as such. It may be genuine or otherwise (1 Thessalonians 5:20-21).

6 For if a woman will not be covered, then let her be shorn! But since it is disgraceful for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered.

6 For if a woman will not be covered, then let her be shorn! But since it is disgraceful for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered.

Although in ancient times the customs of female dress varied, women of all cultures allowed their hair to grow long. Nowhere was short hair the custom for women. Short hair on a woman was a sign of grief or disgrace. Among Jews, Greeks, and Romans, adulteresses sometimes had their hair cropped as an extremely humiliating punishment for their crime. Among the Jews this was done as someone recited the words, “because thou hast departed from the manner of the daughters of Israel, who go with their head covered … therefore that has befallen thee which thou hast chosen.” (6) Sometimes a Greek woman would cut her hair short as a sign of mourning, after the death of a family member. (7) A famous example of this is in the tragic story of Electra, who, after her father was murdered, cropped her hair short in token of her grief. Ancient depictions of Electra show her with her hair cut almost as short as a man’s. In the legend, Electra kept her hair short for years because she was determined to remain in mourning until her brother had avenged her father’s death, but this goes beyond the common custom. Also, there was a religious custom among the Greeks in which people (both male and female) would on certain occasions cut off a lock of hair and offer it to a deity. But there is no reason to think that in the case of women this votive offering involved any general shortening of the hair. (8)

Paul uses two different words here for the removal of the hair. It may be κείρασθαι “shorn” with scissors or ξυρᾶσθαι “shaven” with a razor. Paul uses the words together pleonastically, for emphasis, as in the Septuagint version of Micah 1:16. The word for “disgraceful” here is αἰσχρὸν, which may also be rendered “shameful.” Here Paul seems to anticipate the idea presented more fully in verse 14. The fact that such hair-cropping is universally seen as shameful shows that we naturally expect a woman’s head to be covered. So let her be covered! This is the same word used in 14:35 when Paul says, “it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in church.” Obviously in 14:34-35 γυνή does not mean “wives” only, as if unmarried women were permitted to speak while the married women were to be silent. In ancient times the social status of a married woman was much higher than that of an unmarried woman. Likewise, there is no indication here that Paul thinks only married women should cover their heads.

7 For indeed a man ought not to cover his head, being the image and glory of God; but woman is the glory of man.

8 For man was not made from woman, but woman from man.

9 Neither was man created for woman, but woman for man.

Here Paul begins a new argument in which the headcovering is explained as a symbol. He begins by explaining that man and woman are themselves like symbols, pointing to the purposes for which they were created. When he says that man is the “image” (εἰκὼν) of God he is referring to Genesis 1:26-7, where it says, “Let us make man (Heb. adam) in our image, after our likeness.” When he adds “and glory” (δόξα) he is probably using it in the sense “honor, majesty,” in contrast with the “dishonor” mentioned in verse 4. The majesty of God belongs to men according to the mandate, “Let them have dominion,” and for a man this is part of what it means to be the image of God. The phrase εἰκὼν καὶ δόξα “image and glory” here is probably best understood as a hendiadys, meaning “image of the majesty” (or perhaps “majestic image”). Man was created to symbolize God’s dominion in the earth. (9) But the woman was not created for that iconic purpose, she was created for man. It should be noticed here that Paul does not say that woman is the εἰκὼν καὶ δόξα “image-glory” of man, but only the δόξα “glory” of man. The omission of the qualifying word εἰκὼν is not accidental — the implication is that her “glory” is not iconic or imitative. She is not merely a lesser man, an inferior second-hand copy of the image of God. She symbolizes something altogether different, and this will have consequences for the way in which she ought to worship God.

We should notice at this point that Paul rejects the idea that God has ordained a “unisex” spirituality for Christians. God, who created us male and female, has ordained a masculine spirituality and a feminine spirituality. The influence of the Holy Spirit does not lead us to androgyny, but to a sanctified masculinity for men and a sanctified femininity for women. This is contrary to certain pagan ideas which were becoming popular in places like Corinth in ancient times. Under the gnostic ideologies that arose from Middle Platonism in the first century, the human soul was essentially a spark of the cosmic Reason or mind of God, and the ideal and glorified human soul, liberated from the accidents of the flesh, was androgynous or sexless. Women in their spiritual exercises were supposed to become more like men, and men more like women. This idea is plainly expressed in various pseudo-Christian writings of the gnostic sects in the first three centuries of the Church, and there is good reason to suppose that it was present already in the first generation of the Corinthian congregation. (10) The first-century gnostics, like the “inner light” Quakers and the Transcedentalists of the nineteenth century, maintained that there is “no sex in the soul.” But Paul does not share that opinion.

For Paul, the outstanding fact of woman’s existence is her subordinate position, or rather her subordinate nature, as revealed in the story of creation. It is not merely a matter of position, determined by custom, or an accident of the flesh. A woman is womanly by nature, and by God’s design. She is ontologicaly subordinate to man because she was fashioned for man. In another epistle he says that in this subordination she symbolizes the Church under submission to the authority of God. A well-ordered marriage is a holy mystery that “refers to Christ and to the Church” (Ephesians 5:32). This is the inherent symbolism of man and woman, intended by God from the beginning. Sexual differentiation and identity is not a tragic result of the Fall, to be reversed or transcended by the soul’s escape from the body of flesh (as the gnostics taught), but a consequence of the Creator’s good design.

So in what sense is woman the δόξα of man? It is not an iconic or representational δόξα. If that were the case, we would expect Paul to say that the woman must imitate the man, as some second-rate image of God’s authority. But that is obviously not his intention here. Paul is using the word now in a different sense, in line with a Hellenistic Jewish idiom, in which a woman is said to be the δόξα “honor” of her husband if her womanly virtues and loyal submission redounds to his honor. (11) The best commentary on this phrase is the saying in Proverbs 12:4, “A virtuous woman is a crown to her husband,” as expounded by Matthew Henry:

He that is blessed with a good wife is as happy as if he were upon the throne, for she is no less than a crown to him. A virtuous woman, that is pious and prudent, ingenious and industrious, that is active for the good of her family and looks well to the ways of her household, that makes conscience of her duty in every relation, a woman of spirit, that can bear crosses without disturbance, such a one owns her husband for her head, and therefore she is a crown to him, not only a credit and honour to him, as a crown is an ornament, but supports and keeps up his authority in his family, as a crown is an ensign of power. She is submissive and faithful to him and by her example teaches his children and servants to be so too.

Now, according to the same symbolical manner of thinking, Paul interprets the woman’s headcovering. It is understood to be an emblem of the woman’s submission. It follows, then, that a man should not wear such a headcovering. As the image of God’s authority he should not dress like a woman, because this would involve a symbolical violation of his headship. (12)

10 For this reason the woman should have authority on her head ...

“For this reason” refers to the immediately preceding statements in verses 7-9. The woman should wear the headcovering as a sign of her station, a personal acknowledgement of the fact that she is under the man’s authority (ἐξουσία). And so most English translations add the words “symbol of” before “authority.” The headcovering is a symbol of the man’s authority, not her own, because it would not make sense to draw the conclusion that authority belongs to the woman as an inference from what was said in verses 7-9. (13)

It may be asked, why does Paul use such an ambiguous expression as “authority on her head” instead of saying more plainly “a sign of the man’s authority on her head”? Probably because he is using the phrase ὀφείλει ἡ γυνὴ ἐξουσίαν ἔχειν “a woman should have the ἐξουσία” with some irony here, in response to the libertine Corinthians who maintained that, in the Lord, women should have the ἐξουσία “authority,” “right,” or “permission” to behave as men, without restriction in matters of dress or behavior. The word ἐξουσία is a catchword of the gnostic-libertine party, and so Paul picks it up and turns it against them, as if to say, “women should have an ἐξουσία, yes, the ἐξουσία that God has set over them. Let them wear the headcovering as a sign of the headship of the man, rather than claim an ἐξουσία of their own.” (14)

... because of the angels.

The “angels” are here mentioned as an additional reason for the headcovering. As watchers and agents for God, their attention is especially drawn to spiritual exercises. We might also notice that in Isaiah chapter 6 the seraphs who cried “holy, holy, holy” covered their faces and their feet with their wings in the awful presence of God. It so happens that the Septuagint version has here the word κατακαλυπτων, which Paul has been using. So perhaps Paul’s reference to the angels is meant to recall how the seraphs covered themselves, in which case the idea would be that if the angels themselves do this, how much more should a woman. For further discussion of this phrase see the excursus on the angels.

11 In any case, woman is not independent of man, nor man of woman, in the Lord;

12 for as woman is [made] from man, so man is now [born] through woman. And all things are from God.

Here we translate the word πλὴν “in any case” instead of “nevertheless” because the meaning here is not so much adversative as supplementary. (15) Verses 11-12 reinforce what has already been said by stating the general principle underlying it, that in God’s scheme of things there is really no such thing as an independent woman, or an independent man for that matter. Nothing is truly independent in this world. Therefore let a woman stand before God with a sign of her womanhood, not as a generic and sexless individual. There is nothing to be gained by either sex in pretending that the one can be independent of the other. Notice here that again spiritual androgyny is implicitly rejected. Androgyny would make the man and the woman into independent individuals, twins of the same nature and role, having no need for one another, no complementary relationship or bond. And it is especially to be noted that the gnostic concept of androgynous regeneration is shattered by the words ἐν κυρίῳ here: in the Lord. Paul is speaking of the new life of man and woman in Christ.

13 Judge for yourselves: is it proper for a woman to pray to God with her head uncovered?

Notice that Paul does not say “pray or prophesy” in this verse, as in verses 4 and 5. This indicates that prayer, not prophesying, is the thing foremost in the Apostle’s mind with respect to the women.

14 Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair it is a disgrace for him,

15 but if a woman has long hair, it is her glory? For her hair is given to her for a covering.

In the appeal to “nature” (φύσις) here Paul makes contact with another philosophy of ancient times, known as Stoicism. The Stoics believed that intelligent men could discern what is best in life by examining the laws of nature, without relying on the changeable customs and divers laws made by human rulers. If we consult Nature, we find that it constantly puts visible differences between the male and the female of every species, and it also gives us certain natural inclinations when judging what is proper to each sex. (16) So Paul uses an analogy, comparing the woman’s headcovering to her long hair, which is thought to be more natural for a woman. Though long hair on men is possible, and in some cultures it has been customary for men to have long hair, it is justly regarded as effeminate. It requires much grooming, it interferes with vigorous physical work, and a man with long hair is likely to be seized by it in a fight. It is therefore unmanly by nature. But a woman’s long hair is her glory. Here again is the word δόξα, used opposite ἀτιμία “disgrace,” in the sense of “something bringing honor.” Long and well-kept hair brings praise to a woman because it contributes to her feminine beauty. The headcovering, which covers the head like a woman’s hair, may be seen in the same way. Our natural sense of propriety regarding the hair may therefore be carried over to the headcovering.

Recently some authors have maintained that when Paul says “her hair is given to her for a covering” he is saying that the hair suffices as a covering, and this interpretation has enjoyed some popular currency, but it cannot be the Apostle’s meaning. There was certainly no need for Paul to convince the Corinthian women that they should not crop their hair. That is not an issue at all here. It is simply taken for granted in verses 5 and 6 that such cropped hair would be disgraceful, and so everyone agrees that a woman’s head should be covered. And if there is something especially suitable about a woman’s head being covered, then she should be glad to wear a headcovering in addition to the long hair. But if she does not like a headcovering, well then, let her shear off her hair also! The argument here involves a rhetorical reductio ad absurdum in which there is an analogy made between headcoverings and hair. These verses make no sense otherwise. If by “uncovered” Paul means only a shorn head in the first place, as some would have it, (17) then his argument in verses 5 and 6 amounts to the nonsensical “if a woman will not refrain from cutting off her hair, then let her cut off her hair also.” For this reason Hurley, who does not want to think that Paul is requiring headcoverings here, has resorted to the idea that Paul is saying that a woman’s head is uncovered when her hair is not properly coiffed. (18) But this is very strange, and unlikely in the historical context, where cloth headcoverings and veils were so commonly used. Who can suppose that Paul is making no reference to these when he speaks of headcoverings?

16 But if anyone is inclined to be contentious, we have no such practice, nor do the churches of God.

He thus brings the matter to a conclusion. In addition to the theological and moral reasons for the headcovering, there is also the fact that if the Corinthians were to allow their women to remove the headcovering, this new practice or custom (συνήθειαν) would go against the established custom of Paul and his fellow-workers, the custom which was observed in all the other churches, and which he has delivered to them as one of the παραδόσεις “traditional practices” of the faith (verse 2). A similar appeal to the church-wide παραδόσεις may be seen in 14:33, “As in all the churches of the saints, the women should keep silent,” and the argument there is also ended with a brusque, “if anyone does not recognize this, he is not recognized.” (14:38). Those who continue to challenge the παραδόσεις regarding women after these explanations have been made are to be regarded as obstinate trouble-makers, who deserve no further answer.

Some have strangely interpreted this verse to mean, “But if anyone strongly disagrees with what I have said, rather than make a habit of argument over such unimportant matters let us just say it is a matter of indifference,” etc. But this interpretation fails to take the whole passage seriously as the Word of God. And besides that (which should be enough), it makes no sense either rhetorically or semantically. Paul has devoted some time to this subject because it is important to him, not a matter of indifference; and it makes little sense to speak of a custom of being contentious (φιλόνεικος, lit. “loving strife”), because contentiousness is an attitude or temper, not a custom. There is a good parallel to Paul’s usage of the word φιλόνεικος in Josephus’ work Against Apion. Josephus concludes a series of arguments with the sentence, “I suppose that what I have already said may be sufficient to such as are not very contentious (φιλόνεικος),” (19) and then he continues with even stronger arguments for those who are very contentious. In the same way, Paul reserves the clinching argument for the end. It is an argument from authority. The headcovering practice is a matter of apostolic authority and tradition, and not open to debate. His concluding rebuke of the contentious people in Corinth is meant to cut off debate and settle the issue, not to leave it open. It is quite wrong to say of this last argument of Paul’s that “in the end he admits” that he was merely “rationalizing the customs in which he believes,” (20) as if Paul himself put little store by custom. Rather, Paul considers this to be his strongest point. At the end he harks back to the words with which he opened the subject (“maintain the traditions even as I delivered them to you” in verse 2), and the whole section is thus framed between explicit invocations of tradition.

Application

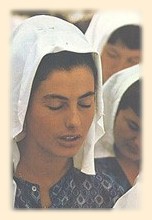

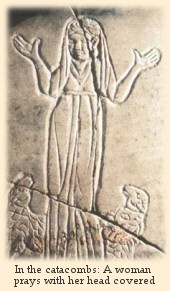

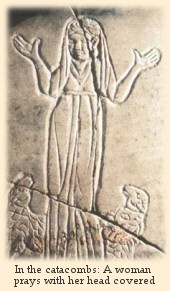

In Ancient Times

There can be little doubt about what application Paul intended the Corinthians to make of this passage. All their women were to cover their heads for prayer at least, both in the assembly and in less formal settings. In view of the customs of the time—in which many women would go about with their heads covered anyway—we might even say that this whole passage has to do not so much with putting on special coverings for prayer as it does with keeping the head covered for prayer. Probably Paul would prefer that a Christian woman would cover her head whenever in public, or whenever she was in the presence of men outside her own family. This would resemble the practice among Jews and others in Asia Minor at the time, where Paul established most of his churches and spent most of his time. The headcovering which Paul has in mind is probably the shawl normally worn over the head by many women at the time. Presumably Paul would not object to local variations of the tradition, as long as something were worn on the head.

There can be little doubt about what application Paul intended the Corinthians to make of this passage. All their women were to cover their heads for prayer at least, both in the assembly and in less formal settings. In view of the customs of the time—in which many women would go about with their heads covered anyway—we might even say that this whole passage has to do not so much with putting on special coverings for prayer as it does with keeping the head covered for prayer. Probably Paul would prefer that a Christian woman would cover her head whenever in public, or whenever she was in the presence of men outside her own family. This would resemble the practice among Jews and others in Asia Minor at the time, where Paul established most of his churches and spent most of his time. The headcovering which Paul has in mind is probably the shawl normally worn over the head by many women at the time. Presumably Paul would not object to local variations of the tradition, as long as something were worn on the head.

The seriousness with which this rule was observed by some Christians in Syria in ancient times may be seen from the apocryphal “Acts of Thomas” (third century), in which there is a very remarkable statement about the fate of bareheaded women in Hell.

And he took me unto another pit, and I stooped and looked and saw mire and worms welling up, and souls wallowing there, and a great gnashing of teeth was heard thence from them. And that man said unto me: These are the souls of women which forsook their husbands and committed adultery with others, and are brought into this torment. Another pit he showed me whereinto I stooped and looked and saw souls hanging, some by the tongue, some by the hair, some by the hands, and some head downward by the feet, and tormented (smoked) with smoke and brimstone; concerning whom that man that was with me answered me: The souls which are hanged by the tongue are slanderers, that uttered lying and shameful words, and were not ashamed, and they that are hanged by the hair are unblushing ones which had no modesty and went about in the world bareheaded (γυμνοκεφαλοι). (21)

For an indication of the application made by Christians in second-century Egypt we have the following passage from Clement of Alexandria.

Woman and man are to go to church decently attired, with natural step, embracing silence, possessing unfeigned love, pure in body, pure in heart, fit to pray to God. Let the woman observe this, further. Let her be entirely covered, unless she happen to be at home. For that style of dress is grave, and protects from being gazed at. And she will never fall, who puts before her eyes modesty, and her shawl; nor will she invite another to fall into sin by uncovering her face. For this is the wish of the Word, since it is becoming for her to pray veiled. (22)

In the West it seems that Christian women ordinarily wore headcoverings also, though without covering any part of the face. At the end of the second century Tertullian (in Carthage) paid much attention to the subject. He wrote one treatise entirely devoted to the question of headcoverings, called On the Veiling of Virgins. We can see from this treatise that in the African province the custom was for adult females to cover their heads with scarves, though Tertullian would like the younger girls to be covered also. Tertullian complains that the headcoverings of some women were too small:

For some, with their turbans and woollen bands, do not veil their head, but bind it up; protected, indeed, in front, but, where the head properly lies, bare. Others are to a certain extent covered over the region of the brain with linen coifs of small dimensions—I suppose for fear of pressing the head—and not reaching quite to the ears. If they are so weak in their hearing as not to be able to hear through a covering, I pity them. Let them know that the whole head constitutes “the woman.” Its limits and boundaries reach as far as the place where the robe begins. The region of the veil is co-extensive with the space covered by the hair when unbound; in order that the necks too may be encircled. For it is they which must be subjected, for the sake of which “power” ought to be “had on the head:” the veil is their yoke. Arabia’s heathen females will be your judges, who cover not only the head, but the face also ... (23)

Of particular interest is the testimony of Tertullian concerning the practice of Corinthian women in his day. He unequivocally asserts that the Corinthians understood Paul to be requiring a headcovering, and that all women (both married and unmarried) of the Corinthian congregation covered their heads:

So, too, did the Corinthians themselves understand him. In fact, at this day the Corinthians do veil their virgins (virgines suas Corinthii velant). What the apostles taught, their disciples approve. (24)

From these sources we may see that anciently the Church in all places did observe the headcovering rule literally enough, with some variations of custom, and with varying degrees of seriousness. The great seriousness of the Syrian church in the matter reflects the strict customs and attitudes about women’s dress which prevailed in all sorts of religious traditions in the East. In Alexandria, where Eastern customs also largely prevailed, it seems that Clement has interpreted Paul as if he were speaking of face-veiling. In both of these, the sources seem to indicate that this practice was understood not really according to Paul’s argument—as a symbolical expression of female subordination—but according to the Eastern cultural standards of decent feminine modesty. The γυμνοκεφαλοι are immodest women, unblushing, inviting sexual attention, etc. But in the West, where women in secular society often went bareheaded, and where face-veiling was not generally practiced, the situation was different. Tertullian, writing to Christians in the African province, complains of the minimal compliance with the rule among Christians, and, although his treatise says a good deal about modesty, he follows Paul by indicating that the headcovering symbolizes submission. This is no coincidence, because Tertullian like Paul was adjuring the women to cover their heads in a context where Eastern customs and ideas did not so prevail as to make theological explanations unnecessary.

We should point out that the wearing of the headcovering in Tertullian’s time was not regarded as a custom peculiar to Christians. In another work he responds to detractors of Christianity by emphasizing the extent to which Christians followed the ordinary customs of secular society:

But we are called upon to answer another charge: we are said to be useless for the ordinary business of life. How can such an accusation be maintained against men who live among yourselves, using the same food and raiment and habits of living, and the same necessaries of life? [Quo pacto homines vobiscum degentes, eiusdem victus, habitus, instructus, eiusdem ad vitam necessitatis?] We are not like the Brahmins, or the Gymnosophists of the Indians, dwellers in the woods, and exiles from ordinary life. (Apology. chap. 42.)

This same point is made in the Epistle to Diognetus (an anonymous fragment, probably from the first half of the third century), whose author shows a particular interest in distinguishing his enlightened philosophical version of Christianity from the more tradition-bound forms of Judaism. He states that Christians “do not practice their religion in the same way as the Jews” (chap. 3), and, “holding aloof from the common silliness and error of the Jews” (chap. 4), they “follow the native customs in dress and food and the other arrangements of life.” (τοῖς ἐγχωρίοις ἔθεσιν ἀκολουθοῦντες ἔν τε ἐσθῆτι καὶ διαίτῃ καὶ τῷ λοιπῳ βίῳ, chap. 5.) But as Tertullian’s treatise on the headcovering reveals, statements like this were not designed to commend mere conformity to whatever fashions happened to prevail in any given time and place. We get the impression that Christians generally acknowledged that true piety involved adherence to certain standards of dress which were traditional for the Church, and a readiness to obey the specific commands of Scripture.

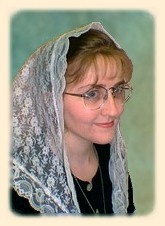

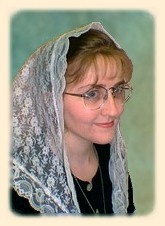

In Modern Times

How are we to apply this rule to ourselves as Christians in the twenty-first century? The whole passage has been treated with some uneasiness in recent times. Since about 1960, not only have hats and scarves gone out of fashion for women in Western nations, but it has become “politically incorrect” to even suggest that women ought to submit to male authority. The very idea that women should be required to wear headcoverings as a sign of their subordination is almost intolerable in the modern context. The interpretation of the passage which gets rid of headcoverings by saying that Paul is only requiring long hair for the women is no solution, because this merely makes the long hair into the symbol of submission, which is no more acceptable to the unisex and egalitarian spirit of the age than the headcoverings were. Long hair on women can no longer be taken for granted, either. We might ask if any of the preachers who explain away the passage with this interpretation have the nerve to tell the women not to cut their hair short, as the Council of Gangra did rather severely in a.d. 370 — “If any woman … cut off her hair, which God has given her as a memorial of subjection, let her be anathema, as one that annuls the decree of subjection.” (25) It appears that in most churches now there is no attempt to preach or honor this passage in any way. The only honest method of dealing with the passage under these circumstances has been to dismiss it as culturally conditioned. In the “old days” women dressed in particular ways that may have been significant at the time, it is said, but the times and fashions have changed, so that headcoverings or bare heads no longer signify anything today. Thus the passage is said to be irrelevent. But this dismissal of the passage will not do, for at least four reasons.

How are we to apply this rule to ourselves as Christians in the twenty-first century? The whole passage has been treated with some uneasiness in recent times. Since about 1960, not only have hats and scarves gone out of fashion for women in Western nations, but it has become “politically incorrect” to even suggest that women ought to submit to male authority. The very idea that women should be required to wear headcoverings as a sign of their subordination is almost intolerable in the modern context. The interpretation of the passage which gets rid of headcoverings by saying that Paul is only requiring long hair for the women is no solution, because this merely makes the long hair into the symbol of submission, which is no more acceptable to the unisex and egalitarian spirit of the age than the headcoverings were. Long hair on women can no longer be taken for granted, either. We might ask if any of the preachers who explain away the passage with this interpretation have the nerve to tell the women not to cut their hair short, as the Council of Gangra did rather severely in a.d. 370 — “If any woman … cut off her hair, which God has given her as a memorial of subjection, let her be anathema, as one that annuls the decree of subjection.” (25) It appears that in most churches now there is no attempt to preach or honor this passage in any way. The only honest method of dealing with the passage under these circumstances has been to dismiss it as culturally conditioned. In the “old days” women dressed in particular ways that may have been significant at the time, it is said, but the times and fashions have changed, so that headcoverings or bare heads no longer signify anything today. Thus the passage is said to be irrelevent. But this dismissal of the passage will not do, for at least four reasons.

1. The headcovering will always signify what Paul has said it signifies. Although it is true that many Christians even in the evangelical churches are not Bible-readers, and have no knowledge of this passage, still its very existence in the Bible ensures that the headcovering will continue to signify submission in churches where the Bible is read. And the Bible ought to be read. Fashions of women’s dress have changed and will continue to change, but Paul in this passage has explained very carefully that the headcovering symbolizes something which does not change. He appeals to custom in the final verse, but here it is not the custom of the surrounding culture to which he refers—but the custom of the churches. And furthermore, in this passage he does not even avail himself of the common Eastern notion that the headcovering is simply a requirement of feminine modesty. Instead, he explains that the headcovering practiced in the churches is emblematic of womanly submission; and he also indicates that this is a symbol which even the angels (who are not subject to changing fashions) take a real interest in. So the practice cannot be dismissed as being merely cultural. And when we consider that the bare-headed fashion of our times came into vogue at the same time that the “women’s liberation” movement began, along with the wearing of pants and the cutting of hair, we ought to pause before we say that these things are really so devoid of symbolism in the culture at large.

2. There was no uniformity in ancient customs, and so it may very well be that the attitudes and arguments of those who today are opposed to this practice, or of those who think it is unimportant, are the very same attitudes and arguments which gave rise to opposition to the practice in first century Corinth. The headcovering was perhaps seen as either “sexist” or of no particular significance, old-fashioned or prudish, savoring of Judaism or some other thing, etc. Paul nevertheless insists upon it. I do not think it is safe to assume that, despite his arguments, Paul’s real intention is merely to affirm and interpret the fashions of his day (especially in Corinth) or that he would affirm in like manner the fashions of modern women if he were writing the letter today. Rather, it seems that Paul wants Christian women to observe a churchly tradition, irrespective of what happens to be in vogue outside the church. (26) Are we really honoring Scripture if we say that, despite its conspicuous absence in the passage, the counsel of cultural conformity is the real and unspoken motive for the ordinance?

On this subject I would like to quote from a little book about the interpretation of the Bible written by R.C. Sproul. In Knowing Scripture, Sproul gives a chapter on “Culture and the Bible,” in which he discusses the treatment of the headcovering passage to illustrate various principles of interpretation and application. He writes:

It is one thing to seek a more lucid understanding of the biblical content by investigating the cultural situation of the first century; it is quite another to interpret the New Testament as if it were merely an echo of the first-century culture. To do so would be to fail to account for the serious conflict the church experienced as it confronted the first-century world. Christians were not thrown to the lions for their penchant for conformity.

Some very subtle means of relativizing the text occur when we read into the text cultural considerations that ought not to be there. For example, with respect to the hair-covering issue in Corinth, numerous commentators on the Epistle point out that the local sign of the prostitute in Corinth was the uncovered head. Therefore, the argument runs, the reason why Paul wanted women to cover their heads was to avoid a scandalous appearance of Christian women in the external guise of prostitutes.

What is wrong with this kind of speculation? The basic problem here is that our reconstructed knowledge of first-century Corinth has led us to supply Paul with a rationale that is foreign to the one he gives himself. In a word, we are not only putting words into the apostle’s mouth, but we are ignoring words that are there. If Paul merely told women in Corinth to cover their heads and gave no rationale for such instruction, we would be strongly inclined to supply it via our cultural knowledge. In this case, however, Paul provides a rationale which is based on an appeal to creation, not to the custom of Corinthian harlots. We must be careful not to let our zeal for knowledge of the culture obscure what is actually said. To subordinate Paul’s stated reason to our speculatively conceived reason is to slander the apostle and turn exegesis into eisogesis.

The creation ordinances are indicators of the transcultural principle. If any biblical principles transcend local customary limits, they are the appeals drawn from creation. (27)

After a few paragraphs Sproul goes on to say, “What if, after careful consideration of a biblical mandate, we remain uncertain as to its character as principle or custom? If we must decide to treat it one way or the other but have no conclusive means to make the decision, what can we do? Here the biblical principle of humility can be helpful. The issue is simple. Would it be better to treat a possible custom as a principle and be guilty of being overscrupulous in our design to obey God? Or would it be better to treat a possible principle as a custom and be guilty of being unscrupulous in demoting a transcendent requirement of God to the level of a mere human convention? I hope the answer is obvious.” (28) Unfortunately it seems that Sproul’s hope is out of place in the easy-going churches of our day. We are quite willing to be guilty of being unscrupulous. We would rather dismiss the apostle’s reproof as “cultually conditioned” and emulate the easy-going Corinthians, who represent the Christian liberty which is so precious to the modern church. But this only shows that we are creatures of a like culture. As Sproul points out in the same work:

It often becomes difficult for me to hear and understand what the Bible is saying because I bring to it a host of extra-biblical assumptions. This is probably the biggest problem of “cultural conditioning” we face. No one of us ever totally escapes being a child of our age ... I am convinced that the problem of the influence of the twentieth-century secular mindset is a far more formidable obstacle to accurate biblical interpretation than is the problem of the conditioning of ancient culture. (29)

3. It is not safe to set aside any portion of Scripture, especially of the New Testament, without compelling reasons. If we can dismiss this portion of Scripture so lightly, we can dismiss anything in Scripture which disagrees with the fashions (both sartorial and moral) of our times. A passage which on its face offers what may even be called moral reasons for this garment is being dismissed as culturally relative and now obsolete. This is a very dangerous hermeneutical precedent, and I cannot believe that the avoidance of unstylish headcoverings for the ladies is worth the trouble we will get from compromised principles of interpretation.

4. We should not be asking how much we are allowed to ignore the literal instructions of this passage or any other passage of Scripture so long as we claim to be observing the “spirit.” We should be asking how we may best obey it both in spirit and in the letter.

For these reasons and others I think it would be best if Christian women were to cover their heads, just as Paul directed. Symbols have a powerful effect on our lives, and it is not safe to treat them with contempt, especially when the symbol in question has been appointed in Scripture itself.

The old claim that fashion in clothing is morally neutral and essentially devoid of symbolism has now been destroyed by recent downgrade trends in women’s fashion, and Christian parents are keenly aware of the significance of clothing in the case of their teenage daughters. Moreover, the feminist movement (which knows very well what clothing may say about a woman) has created a social environment which is so inimical to Christian values that many Christian women now finally recognize that they cannot allow themselves to be creatures of fashion. And so the church is ripe for a reconsideration of this whole question. In any case, church leaders and evangelical authors who have been discouraging the use of headcoverings should reconsider their opposition to it.

“If anyone thinks that he is a prophet, or spiritual, he should acknowledge that the things I am writing to you are a commandment of the Lord.” (I Corinthians 14:37)

Applications for Men

Although the emphasis is on women and their attire in this passage, the passage does contain some statements which men should take to heart and apply to themselves.

First there are the implications of the uncovered head. Paul states that the reason for this bareheadedness is that the Christian man must exhibit the “image-glory of God,” which we have understood in the sense that he must identify with and imitate God, as ruler of the creation. This is no small responsibility for men. We are all familiar with the biblical teaching that men must obey and serve God. The Bible in many places calls God’s people His servants, and the word usually translated “servants” really means slaves. But even so, where Christian men are concerned, the biblical concept of our relationship to God is more perfectly expressed as one of sonship. And a son is not a slave; he both obeys and imitates his Father. The incongruity of this metaphor in relation to women is obvious enough. A woman should not be asked to think of herself as a son who must imitate the Father. But this is what Christian men are called to do. A manly soul is not content to obey, he goes beyond that and makes his royal Father’s interests his own. He inherits the dominion. There is therefore a certain emulation of God proper for men which is not characteristic of female piety. This stance, symbolized by the uncovered head, is going to have consequences for the way in which a man worships God and lives out his faith.

Works Cited in the Notes

Athanasius. Athanasius of Alexandria, De Incarnatione Verbi Dei: Athanasius on the Incarnation, Translated with an Introduction, Analysis, Synopsis and Notes, by T. Herbert Bindley, M.A. (Christian Classics Series III). London: Religious Tract Society, n.d. [ca. 1885].

Barrett. Charles K. Barrett, Commentary on the First Epistle to the Corinthians (New York: Harper and Row, 1968).

Bauer. Walter Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, translated by William F. Arndt and F. Wilbur Gingrich, second edition revised and augmented by F. Wilbur Gingrich and Frederick W. Danker, from Walter Bauer’s fifth edition, 1958 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979).

Blundell. Sue Blundell, Women in Ancient Greece (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995).

Cheetham. Samuel Cheetham, “Dress,” in Dictionary of Christian Antiquities, edited by William Smith and Samuel Cheetham, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1875), pp. 580-83.

Clark. Stephen B. Clark, Man and Woman in Christ: An Examination of the Roles of Men and Women in Light of Scripture and the Social Sciences (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Servant Books, 1980).

Clement of Alexandria, Paedagogus [The Instructor], in Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers down to A.D. 325, vol. 2: Fathers of the Second Century: Hermas, Tatian, Athenagoras, Theophilus, and Clement of Alexandria (Reprint ed., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1962).

Conzelmann. Hans Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians, in the Hermeneia commentary series (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975), translated from the German Der erste Brief an die Korinther, 1st edition (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1969).

Edersheim. Alfred Edersheim, Sketches of Jewish Social Life in the Days of Christ (London: Religious Tract Society, 1876).

Erdman. Charles R. Erdman, The First Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians: An Exposition (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1928).

Fee. Gordon D. Fee, The First Epistle to the Corinthians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987).

Foerster. Werner Foerster, “ἐξουσία,” in volume 2 of Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964), pp. 560-75.

Craig. Clarence T. Craig and John Short, The First Epistle to the Corinthians: Introduction and Exegesis by Clarence T. Craig, Exposition by John Short, in volume 10 of The Interpreter’s Bible (New York: Abingdon Press, 1953).

Daly. Mary Daly, Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation (Boston: Beacon, 1973).

Grudem, 2001. Wayne Grudem, “The Meaning of κεφαλη (‘Head’): An Evaluation of New Evidence, Real and Alleged,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 44/1 (March 2001), pp. 25-65.

Grudem, 2002. Wayne Grudem, ed., Biblical Foundations for Manhood and Womanhood (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 2002).

Grudem and Piper, Recovering. Wayne Grudem and John Piper, eds., Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 1991).

Grudem and Piper, Questions. Wayne Grudem and John Piper, Fifty Crucial Questions. An Overview of Central Concerns about Manhood and Womanhood (Westchester, Illinois: Crossway Books, 1990).

Harris. M. J. Harris, “Prepositions and Theology in the Greek New Testament,” in vol. 3 of The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978), p. 1171-1215.

Hays. Richard B. Hays, First Corinthians, in the series Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: John Knox Press, 1997).

Hodge. Charles Hodge, An Exposition of the First Epistle to the Corinthians (New York: R. Carter, 1857).

Hurd. John C. Hurd, The Origin of I Corinthians (London: S.P.C.K., 1965).

Hurley, 1973. James B. Hurley, “Did Paul Require Veils or the Silence of Women? A Consideration of 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 and 1 Corinthians 14:33b-36.” Westminster Theological Journal 35/2 (Winter 1973), pp. 190-220.

Hurley, 1981. James B. Hurley, Man and Woman in Biblical Perspective (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1981).

James. M.R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924).

Kendrick. W. Gerald Kendrick, “Authority, Women, and Angels: Translating 1 Corinthians 11:10,” The Bible Translator 46 (July 1995), p. 337.

Kittel. Gerhard Kittel, “δόξα,” in volume 2 of Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965), pp. 233-37.

Lenski. R.C.H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. Paul’s First and Second Epistles to the Corinthians (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1963. Reprinted from the original edition of 1937).

Martin. William J. Martin, “1 Corinthians 11:2-16: An Interpretation,” in Apostolic History and the Gospel: Biblical and Historical Essays Presented to F. F. Bruce on his 60th Birthday, eds., W. Ward Gasque and Ralph P. Martin (Exeter: The Paternoster Press, 1970), pp. 231-241.

Mattei. Eva Schulz-Fluegel and Paul Mattei, Tertullien: Le voile des vierges. Sources Chretiennes 424. (Paris: Editions de Cerf, 1997).

Meyer. H.A.W. Meyer, Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Corinthians. Translated from the Fifth Edition of the German by Rev. D. Douglas Bannerman (New York: Funk & Wagnals, 1884).

Noy. David Noy, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe: Italy (excluding the City of Rome), Spain and Gaul (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Philo of Alexandria, The Works of Philo, translated by C.D. Yonge. New Updated Edition, edited by David M. Scholer (Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson, 1993).

Ramsay. William Ramsay, The Cities of St. Paul: Their Influences on his Life and Thought (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1907).

Robertson. A.T. Robertson, Word Pictures in the New Testament 6 vols. (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1930-1933).

Rouse. William H.D. Rouse, Greek Votive Offerings: An Essay in the History of Greek Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 1902).

Sanders. E.P. Sanders, Paul, the Law, and the Jewish People (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983).

Schlier. Heinrich Schlier, “κεφαλη,” in volume 3 of Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965), pp. 673-82.

Sproul. R.C. Sproul, Knowing Scripture (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1977).

Tertullian, “On the Veiling of Virgins,” translated by S. Thelwall, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, volume iv, ed. A. Roberts and J. Donaldson (Edinburgh, 1885).

Thayer. Joseph Henry Thayer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, 4th edition (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1901).

Thiselton. Anthony Thiselton, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000). ISBN: 0802824498.

Van der Horst. Pieter Willem van der Horst, Ancient Jewish Epitaphs: An Introductory Survey of a Millennium of Jewish Funerary Epigraphy (Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 1991).

Ware. Bruce A. Ware, “Male and Female Complementarity and the Image of God,” Journal for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood 7/1 (Spring 2002), pp. 14-23.

Winter, 2001. Bruce W. Winter, After Paul Left Corinth: The Influence of Secular Ethics and Social Change (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001).

Winter, 2003. Bruce W. Winter, Roman Wives, Roman Widows: The Appearance of New Women and the Pauline Communities (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003).

NOTES

1. Paul begins this new section of the letter on a conciliatory note because he is employing one of the conventions of classical rhetoric, in which the exordium (preamble) contains a captatio benevolentiae — a “capturing of the good will” of the audience. The same rhetorical feature may be seen in several of his letters, and in his speeches in Acts (cf. the opening of his famous speech on Mars’ Hill, recorded in Acts 17:22, “Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious”). There is no need to ask what traditions in particular he may be referring to here, because he is appealing in a very general way to the willingness of the Corinthians to maintain the Apostolic traditions (note the plural). Anthony Thiselton is on the wrong track when he speculates that “part of the observed traditions (παραδόσεις, 11:2) probably included the Christian practice of women leading a congregation in the Godward ministry of prayer, and leading in preaching a pastorally applied message or discourse from God” (p. 828). The idea that Paul could be referring to any such tradition stemming from himself in 11:2 is ruled out by 1 Corinthians 14:34-35 and 1 Timothy 2:11-14 (the latter of which has several things in common with the present passage), and so it can only be maintained by attributing these to another author, or to a change in Paul’s attitude. If any particular tradition is meant, it is of course the headcovering custom. John C. Hurd, in his book The Origin of I Corinthians (London: S.P.C.K., 1965), wrongly speculates that in 11:2 Paul is referring to a Corinthian claim that Paul himself established a tradition of allowing the women to go without headcoverings. Hurd believes that Paul changed his position on this, while the Corinthians were holding to his original practice. But this speculation seems to be ruled out by verse 16, which returns to the subject of customary practice with an emphatic “we have no such practice” (of removing the headcovering).

2. Egalitarian scholars such as Gordon Fee have not been able to make sense of this passage, and in particular they are incapable of giving an adequate explanation for the sentence in verse 3, which is the keystone verse of the passage. Fee tries to dismiss it by calling it a “theologoumenon” (theological statement) that has no real importance in the passage. He surmises that the statement about headship in verse 3 is only a convenient rhetorical way of approaching the headcovering issue broached in verses 4-5, after which it simply drops from view. But how can he say that verses 7-9 do not resume the thought expressed in verse 3? He lamely states that after verses 4-5 “there is no further direct reference” to the “theologoumenon” in verse 3, by which he apparently means that the saying is not actually repeated; but even so, he is forced to concede (in a footnote) that in verse 8 there is at least an “oblique reference” to verse 3 (p. 501). Actually, he depends upon this connection in his discussion of the meaning of the word κεφαλη (lit. “head”). Like other egalitarians before him, he rejects the whole concept of headship and he argues that in verse 3 the word means “source” rather than “authority.” Although we have good attestation for the use of this word as a hierarchical metaphor meaning “authority” in ancient literature, Fee asserts that this usage is “an exceptional usage and not part of the ordinary range of meanings for the Greek word” (p. 503). He further asserts that the sense “source,” especially “source of life,” is “almost certainly the only one the Corinthians would have grasped.” But this assertion has virtually no basis in the available evidence. It has so little basis that Bauer’s Lexicon does not even mention “source” as a figurative meaning of the word. How can Fee make such an assertion, then? In his handling of this matter, he is apparently indebted to Barrett’s commentary, where we find a more nuanced and cautious treatment. Barrett writes:

In this verse (which is to be contrasted with 4, 7, 10 below) the word head (κεφαλη) is evidently used in a transferred sense. In the Old Testament head (rosh, sometimes but by no means always translated into Greek as κεφαλη) may refer to the ruler of a community (e.g. Judges x. 18); this use, however, though it was adopted in Greek-speaking Judaism, was not a native meaning of the Greek word (for details see H. Schlier, in T.W.N.T. iii. 674 f.). In Greek usage the word, when metaphorical, may apply to the outstanding and determining part of a whole, but also to origin (e.g. in the plural, to the source of a river, as in Herodotus iv. 91). In this sense it is used theologically, as in an Orphic fragment (21a): Zeus is the head, Zeus the middle, and from Zeus all things are completed (Ζευς κεφαλη, Ζευς μεσσα, Διος δ᾽ εκ παντα τελειται ; that some MSS. have αρχη instead of κεφαλη adds to its significance; see also S. Bedale in J.T.S. v (new series), 211-15). That this is the sense of the word here is strongly suggested by verse 8 f. Paul does not say that man is the lord (κυριος) of the woman; he says that he is the origin of her being. (p. 248)

This is more cautious than what we read in Fee, but still very misleading, because Barrett is relying upon only two occurrences where the word may be understood as “origin” from a mass of lexicographical evidence that does not otherwise support such a meaning. The one from Herodotus is plural, and it seems to be an idiom. He interprets the Orphic fragment very superficially, neglecting the evident fact that here κεφαλη is being used as a technical term in the context of some extravagant pagan cosmogony, in which it seems to mean “beginning” (there is no good reason to interpret this further as “source”) and “the outstanding and determining part of a whole,” and much more besides. In any case, even if it could be established that “source” is the meaning here, it is inappropriate for Fee to cite this text as a basis for his statement about “the ordinary range of meanings for the Greek word,” because this is no ordinary text. Schlier’s interesting discussion of this Orphic fragment in his Theological Dictionary of the New Testament article explains that the cosmological headship spoken of here belongs to the sphere of a Persian-inspired “aeon myth” in which a heavenly aeon produces subordinate beings through emanations, over which the aeon has a kind of ontological supremacy. Further on in the article he brings this “aeon conception” into relation with Paul’s usage in 1 Corinthians 11 because he supposes that Paul is making use of it in an attenuated way. He suggests that when Paul says that “the head of the woman is the man” he refers not only to the woman’s subjection but also to the fact that “the origin and raison d’etre of woman are to be found in man,” because here “κεφαλη implies one who stands over another in the sense of being the ground of his being. Paul could have used αρχη if there had not been a closer personal relationship in κεφαλη” (p. 679). He also points out that “the basis of the relation of the body to the Head is always the obedience of subjection” (p. 680). He is not the least bit interested in putting some egalitarian meaning on the word in 1 Corinthians 11. If Fee wants to make so much of the usage of κεφαλη in this Orphic fragment in his egalitarian interpretation of 1 Corinthians 11:3, he really ought to interact with Schlier’s treatment of it, which is much more nuanced and satisfactory. But there really is no warrant for fetching Paul’s meaning from this Orphic text. There is no good reason to doubt that when he says, “the head of every man is Christ, the head of the woman is the man, and the head of Christ is God,” he is using the word κεφαλη in the well-attested metaphorical sense of “ruler.” (For Hellenistic Jewish examples of this usage, which may be regarded as a Hebraism, see the Septuagint’s rendering κεφαλη in Judges 10:18; 11:8, 9, 11, where the Hebrew text has ראש rosh, with the meaning “ruler,” and also Paul’s use of the word to denote the authority of Christ in Ephesians 1:22; 4:15; 5:23; Colossians 1:18; 2:19.) The verses which follow show plainly enough that questions of authority are his main concern, and this becomes especially clear in verse 10, where it is explained that the headcovering represents ἐξουσίαν “authority.” In verse 3, he uses the word κεφαλη in this metaphorical way instead of κυριος (lord) or αρχων (ruler) for two reasons: he has in view the symbolical explanation of the head covering which he is going to offer in the passage, and so he uses the word for “head” here as a metaphor that lends itself to that purpose; and he wants to suggest that the authority of which he speaks is not an authority arbitrarily imposed upon someone, but the kind of authority which naturally belongs to a “head” that is in organic unity with its “body.”

Ultimately the egalitarian interpreters fail to make sense of the passage even if κεφαλη is understood as “source,” because this only raises the question of why Paul is talking about “sources.” What importance does he see in the fact that the man is the “source” of the woman? The egalitarians cannot tell us why it matters. Fee can only say very obscurely that it has something to do with “relationships that are predicated on one’s being the source of the other’s existence” (p. 503). This kind of transparently evasive comment is typical of the “evangelical” egalitarians. More honesty is found among openly liberal egalitarians who do not pretend to accept the authority of the Bible, and who freely admit that Paul’s teaching is “sexist”—Richard B. Hays, for instance, who writes, “Any honest appraisal of 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 will require both teacher and students to confront the patriarchal implications of verses 3 and 7-9. Such implications cannot be explained away by some technical move, such as translating kephale as ‘source,’ rather than ‘head,’ because the patriarchal assumptions are imbedded in the structure of Paul’s argument.” (p. 192.) Hays supposes that sexual egalitarianism was the main source of the headcovering problem in Corinth. He explains that for the Corinthian women a headcovering “symbolized their femininity and simultaneously their inferior status as women,” and “to throw off this covering was to throw off a symbol of confinement and to enter the realm of freedom and autonomy traditionally accorded only to men.” (p. 184.)

For a very thorough discussion of the word κεφαλη in the New Testament and in Greek literature generally see Wayne Grudem, “The Meaning of κεφαλη (‘Head’): An Evaluation of New Evidence, Real and Alleged,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 44/1 (March 2001), pp. 25-65 ; reprinted in Wayne Grudem, ed., Biblical Foundations for Manhood and Womanhood (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 2002), pp. 145-202. An earlier and less technical article is Grudem’s The Meaning of Kephale (Head): A Response to Recent Studies,” in Wayne Grudem and John Piper, eds., Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 1991). Grudem interacts very patiently with all the recent writers who have tried to get rid of the man’s “headship” in this passage by interpreting the word κεφαλη as “source.”

3. Sue Blundell, Women in Ancient Greece (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 148. “the hetaerae ... represented the only significant group of economically independent women in classical Athens.”