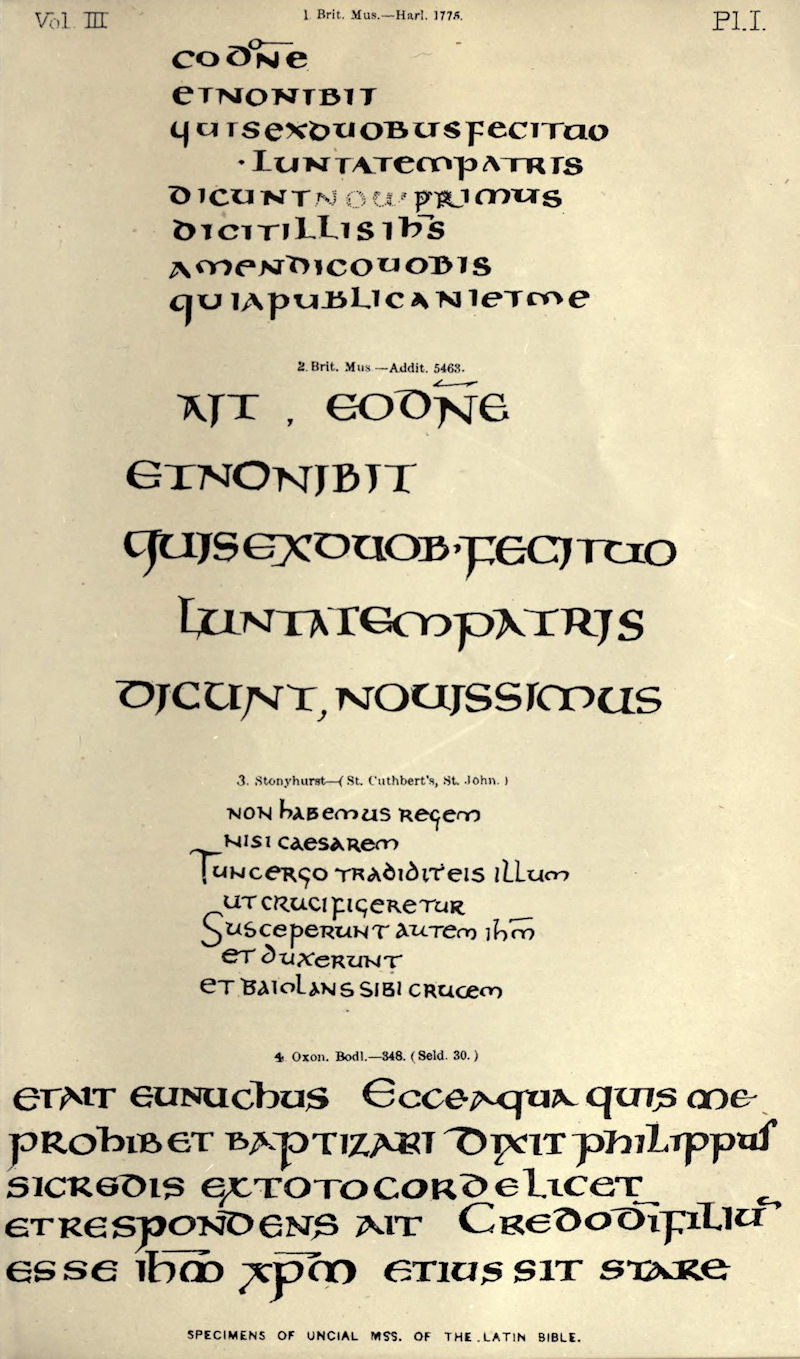

Plate I

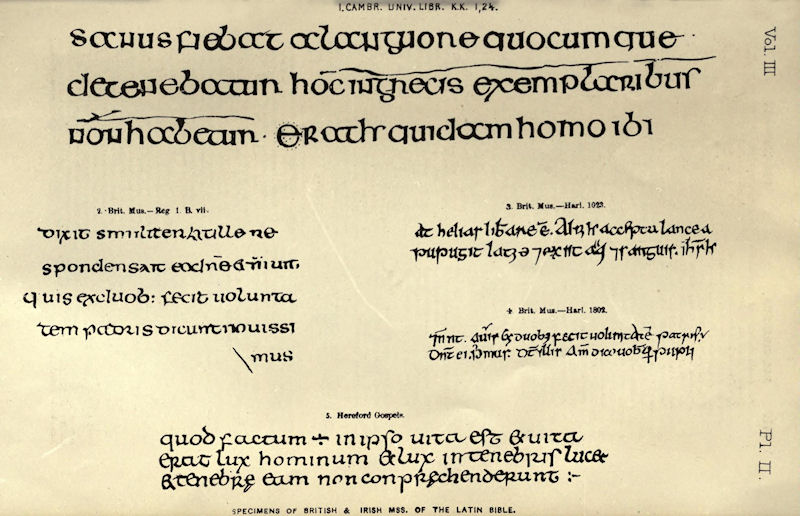

Plate II

| Bible Research > Ancient Versions > Latin > Westcott |

The following article on the Old Latin and Vulgate versions of the Bible by B. F. Westcott is reproduced from Dr. William Smith’s Dictionary of the Bible … revised and edited by Prof. H.B. Hackett … Volume IV (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1881), pp. 3451-82. I have transferred the footnotes to the end of the article, numbered them sequentially, and abbreviated notes 33 and 49. —M.D.M.

by B.F. Westcott

The influence which the Latin Versions of the Bible have exercised upon Western Christianity is scarcely less than that of the LXX. upon the Greek churches. But both the Greek and the Latin Vulgates have been long neglected. The revival of letters, bringing with it the study of the original texts of Holy Scripture, checked for a time the study of these two great bulwarks of the Greek and Latin churches, for the LXX. in fact belongs rather to the history of Christianity than to the history of Judaism, and, in spite of recent labors, their importance is even now hardly recognized. In the case of the Vulgate, ecclesiastical controversies have still further impeded all efforts of liberal criticism. The Romanist (till lately) regarded the Clementine text as fixed beyond appeal; the Protestant shrank from examining a subject which seemed to belong peculiarly to the Romanist. Yet, apart from all polemical questions, the Vulgate should have a very deep interest for all the Western churches. For many centuries it was the only Bible generally used; and, directly or indirectly, it is the real parent of all the vernacular versions of Western Europe. The Gothic Version of Ulphilas alone is independent of it, for the Slavonic and modern Russian versions are necessarily not taken into account. With England it has a peculiarly close connection. The earliest translations made from it were the (lost) books of Bede, and the Glosses on the Psalms and Gospels of the 8th and 9th centuries (ed. Thorpe, Lond. 1835, 1842). [Here Westcott can only be referring to Thorpe’s editions of the West-Saxon Psalms and Gospels, but these were not glosses, and they were most probably done in the tenth century. — M.D.M.] In the 10th century Ælfric translated considerable portions of the O. T. (Heptateuchus, etc., ed. Thwaites, Oxon. 1698). But the most important monument of its influence is the great English Version of Wycliffe (1324-1384, ed. Forshall and Madden, Oxfd. 1850), which is a literal rendering of the current Vulgate text. In the age of the Reformation the Vulgate was rather the guide than the source of the popular versions. The Romanist translations into German (Michaelis, ed. Marsh, ii. 107), French, Italian, and Spanish, were naturally derived from the Vulgate (R. Simon, Hist. Crit. N. T. Cap. 28, 29, 40, 41). Of others, that of Luther (N. T. in 1523) was the most important, and in this the Vulgate had great weight, though it was made with such use of the originals as was possible. From Luther the influence of the Latin passed to our own Authorized Version. Tyndal had spent some time abroad, and was acquainted with Luther before he published his version of the N. T. in 1526. Tyndal’s version of the O. T., which was unfinished at the time of his martyrdom (1536), was completed by Coverdale, and in this the influence of the Latin and German translations was predominant. A proof of this remains in the Psalter of the Prayer Book, which was taken from the “Great English Bible” (1539, 1540), which was merely a new edition of that called Matthew’s, which was itself taken from Tyndal and Coverdale. This version of the Psalms follows the Gallican Psalter, a revision of the Old Latin, made by Jerome, and afterwards introduced into his new translation (comp. § 22), and differs in many respects from the Hebrew text (e. g. Ps. xiv.). It would be out of place to follow this question into detail here. It is enough to remember that the first translators of our Bible had been familiarized with the Vulgate from their youth, and could not have cast off the influence of early association. But the claims of the Vulgate to the attention of scholars rest on wider grounds. It is not only the source of our current theological terminology, but it is, in one shape or other, the most important early witness to the text and interpretation of the whole Bible. The materials available for the accurate study of it are unfortunately at present as scanty as those yet unexamined are rich and varied (comp. § 30). The chief original works bearing on the Vulgate generally are —

R. Simon, Histoire Critique du V. T. 1678-1685: N. T. 1689-1693.

Hody, De Bibliorum textibus originalibus, Oxon. 1705.

Martianay, Hieron. Opp. (Paris, 1693, with the prefaces and additions of Vallarsi, Verona, 1734, and Maffei, Venice, 1767).

Bianchini (Blanchinus not Blanchini), Vindiciae Canon. SS. Vulg. Lat. Edit. Romae, 1740.

Bukentop, Lux de Luce … Bruxellis, 1710.

Sabatier, Bibl. SS. Lat. Vers. Ant., Remis, 1743.

Van Ess, Pragmatisch-kritische Gesch. d. Vulg. Tübingen, 1824.

Vercellone, Variae Lectiones Vulg. Lat. Bibliorum, tom. i, Romae, 1860; tom. ii. pars prior, 1862.

In addition to these there are the controversial works of Mariana, Bellarmin, Whitaker, Fulke, etc., and numerous essays by Calmet, D. Schulz, Fleck, Riegler, etc., and in the N. T. the labors of Bentley, Sanftl, Griesbach, Schulz, Lachmann, Tregelles, and Tischendorf, have collected a great amount of critical materials. But it is not too much to say that the noble work of Vercellone has made an epoch in the study of the Vulgate, and the chief results which follow from the first installment of his collations are here for the first time incorporated in its history. The subject will be treated under the following heads: —

I. The Origin and History of the Name Vulgate. §§ 1-3.

II. The Old Latin Versions. §§ 4-13. Origin, 4, 5. Character, 6. Canon, 7. Revisions: Itala, 8-11. Remains, 12, 13.

III. The Labors of Jerome. §§ 14-20. Occasion, 14. Revision of Old Latin of N. T., 15-17. Gospels, 15, 16. Acts, Epistles, etc., 17. Revision of O. T. from the LXX., 18, 19. Translation of O. T. from the Hebrew, 20.

IV. The History of Jerome’s Translation to the Introduction of Printing. §§ 21-24. Corruption of Jerome’s text, 21, 22. Revision of Alcuin, 23. Later revisions: divisions of the text, 24.

V. The History of the Printed Text. §§ 25-29. Early editions, 25. The Sixtine and Clementine Vulgates, 26. Their relative merits, 27. Later editions, 28, 29.

VI. The Materials for the Revision of Jerome’s Text. §§ 30-32. MSS. of O.T., 30, 31. OfN. T., 32.

VII. The Critical Value of the Latin Versions. §§ 33-39. In O.T., 33. In N. T., 34-38. Jerome’s Revision, 34-36. The Old Latin, 37. Interpretation, 39.

VIII. The Language of the Latin Versions, §§ 40-45. Provincialisms, 41, 42. Graecisms, 43. Influence on Modem Language, 45.

I. The Origin and History of the Name Vulgate. — 1. The name Vulgate, which is equivalent to Vulgata editio (the current text of Holy Scripture), has necessarily been used differently in various ages of the Church. There can be no doubt that the phrase originally answered to the κοινὴ ἔκδοσις of the Greek Scriptures. In this sense it is used constantly by Jerome in his Commentaries, and his language explains sufficiently the origin of the term: “Hoc juxta LXX. interpretes diximus, quorum editio toto orbe vulgata est” (Hieron. Comm. in Is. lxv. 20). “Multum in hoc loco LXX. editio Hebraicumque discordant. Primum ergo de Vulgata editione tractabimus et postea sequemur ordinem veritatis” (id. xxx. 22). In some places Jerome distinctly quotes the Greek text: “Porro in editione Vulgata dupliciter legimus; quidam enim codices habent, δῆλοί εἰσιν, hoc est, manifesti sunt: alii δειλαῖοί εἰσιν, hoc est meticulosi sive miseri sunt” (Comm. in Osee, vii. 13; comp. 8-11, etc.). But generally he regards the Old Latin, which was rendered from the LXX., as substantially identical with it, and thus introduces Latin quotations under the name of the LXX. or Vulgata editio: “… miror quomodo vulgata editio … testimonium alia interpretatione subverterit: Congregabor et glorificabor coram Domino … Illud autem quod in LXX. legitur: Congregabor et glorificabor coram Domino …” (Comm. in Is. xlix. 5). So again: “Philisthaeos … alienigenas Vulgata scribit editio” (ibid. xiv. 29). “… Palsestinis, quos indifferenter LXX. alienigenas vocant” (in Ezek. xvi. 27). In this way the transference of the name from the current Greek text to the current Latin text became easy and natural; but there does not appear to be any instance in the age of Jerome of the application of the term to the Latin Version of the O. T. without regard to its derivation from the LXX., or to that of the N. T.

2. Yet more: as the phrase κοινὴ ἔκδοσις came to signify an uncorrected (and so corrupt) text, the same secondary meaning was attached to vulgata editio. Thus in some places the vulgata editio stands in contrast with the true Hexaplaric text of the LXX. One passage will place this in the clearest light: “… breviter admoneo aliam esse editionem quam Origenes et Caesariensis Eusebius, omnesque Graeciae translatores κοινὴν, id est, communem appellant, atque vulgatam, et a plerisque nunc Λουκινὸς dicitur; aliam LXX. interpretum quae in ἑξαπλοῖς codicibus reperitur, et a nobis in Latinum sermonem fideliter versa est … Κοινη autem ista, hoc est, Communis editio, ipsa est quae et LXX., sed hoc interest inter utramque, quod κοινὴ pro locis et temporibus et pro voluntate scriptorum vetus corrupta editio est; ea autem quae habetur in ἑξαπλοῖς et quam nos vertimus, ipsa est quae in eruditorum libris incorrupta et immaculata LXX. interpretum translatio reservatur” (Ep. cvi. ad Sun. et Fret. §2).

3. This use of the phrase Vulgata editio to describe the LXX. (and the Latin Version of the LXX.) was continued to later times. It is supported by the authority of Augustine, Ado of Vienne (a.d. 860), R. Bacon, etc.; and Bellarmin distinctly recognizes the application of the term, so that Van Ess is justified in saying that the Council of Trent erred in a point of history when they described Jerome’s Version as “vetus et vulgata editio, quae longo tot saeculorum usu in ipsa ecclesia probata est” (Van Ess, Gesch. 34). As a general rule, the Latin Fathers speak of Jerome’s Version as “our” version (nostra editio, nostri codices); but it was not unnatural that the Tridentine Fathers (as many later scholars) should be misled by the associations of their own time, and adapt to new circumstances terms which had grown obsolete in their original sense. And when the difference of the (Greek) “Vulgate” of the early Church, and the (Latin) “Vulgate” of the modern Roman Church has once been apprehended, no further difficulty need arise from the identity of name. (Compare Augustine, Ed. Benedict. Paris, 1836, tom. V. p. xxxiii.; Sabatier, i. 792; Van Ess, Gesch. 24-42, who gives very full and conclusive references, though he fails to perceive that the Old Latin was practically identified with the LXX.)

II. The Old Latin Versions. —4. The history of the earliest Latin Version of the Bible is lost in complete obscurity. All that can be affirmed with certainty is that it was made in Africa. 1 During the first two centuries the Church of Rome, to which we naturally look for the source of the version now identified with it, was essentially Greek. The Roman bishops bear Greek names; the earliest Roman liturgy was Greek; the few remains of the Christian literature of Rome are Greek. 2 The same remark holds true of Gaul (comp. Westcott, General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament, pp. 269, 270, and reff.); but the Church of N. Africa seems to have been Latin-speaking from the first. At what date this Church was founded is uncertain. A passage of Augustine (c. Donat. Ep. 37) seems to imply that Africa was converted late; but if so, the Gospel spread there with remarkable rapidity. At the end of the second century Christians were found in every rank, and in every place; and the master-spirit of Tertullian, the first of the Latin Fathers, was then raised up to give utterance to the passionate thoughts of his native Church. It is therefore from Tertullian that we must seek the earliest testimony to the existence and character of the Old Latin (Vetus Latina).

5. On the first point the evidence of Tertullian, if candidly examined, is decisive. He distinctly recognizes the general currency of a Latin Version of the N. T., though not necessarily of every book at present included in the Canon, which even in his time had been able to mould the popular language (adv. Prax. 5: In usu est nostrorum per simplicitatem interpretationis … De Monog. 11: Sciamus plane non sic esse in Graeco authentico quomodo in usum exiit per duarum syllabarum aut callidam aut simplicem eversionem …). This was characterized by a “rudeness” and “simplicity,” which seems to point to the nature of its origin. In the words of Augustine (De doctr. Christ, ii. 16 (11)), “any one in the first ages of Christianity who gained possession of a Greek MS., and fancied that he had a fair knowledge of Greek and Latin, ventured to translate it.” (Qui scripturas ex Hebraea lingua in Graecam verterunt numerari possunt; Latini autem interpretes nullo modo. Ut enim cuivis primis fidei temporibus in manus venit Codex Graecus, et aliquantulum facultatis sibi utriusque linguae habere videbatur, ausus est interpretari.) 3 Thus the version of the N. T. appears to have arisen from individual and successive efforts; but it does not follow by any means that numerous versions were simultaneously circulated, or that the several parts of the version were made independently. 4 Even if it had been so, the exigencies of the public service must soon have given definiteness and substantial unity to the fragmentary labors of individuals. The work of private hands would necessarily be subject to revision for ecclesiastical use. The separate books would be united in a volume; and thus a standard text of the whole collection would be established. With regard to the O.T. the case is less clear. It is probable that the Jews who were settled in N. Africa were confined to the Greek towns; otherwise it might be supposed that the Latin Version of the O. T. is in part anterior to the Christian era, and that (as in the case of Greek) a preparation for a Christian Latin dialect was already made when the Gospel was introduced into Africa. However this may have been, the substantial similarity of the different parts of the Old and New Testaments establishes a real connection between them, and justifies the belief that there was one popular Latin Version of the Bible current in Africa in the last quarter of the second century. Many words which are either Greek (machaera, sophia, perizoma, poderis, agonizo, etc.) or literal translations of Greek forms (vivifico, justifico, etc.) abound in both, and explain what Tertullian meant when he spoke of the “simplicity” of the translation (compare below § 43).

6. The exact literality of the Old Version was not confined to the most minute observance of order and the accurate reflection of the words of the original: in many cases the very forms of Greek construction were retained in violation of Latin usage. A few examples of these singular anomalies will convey a better idea of the absolute certainty with which the Latin commonly indicates the text which the translator had before him, than any general statements: Matt. iv. 13, habitavit in Capharnaum maritimam; id. 15, terra Neptalim viam maris; id. 25, ab Jerosolymis … et trans Jordanem; v. 22, reus erit in gehennam ignis; vi. 19, ubi tinea et comestura exterminat. Mark xii. 31, majus horum praeceptorum aliud non est. Luke x. 19, nihil vos nocebit. Acts xix. 26, non solum Ephesi sed paene totius Asiae. Rom. ii. 15, inter se cogitationum accusantium vel etiam defendentium. 1 Cor. vii. 32, solicitus est quae sunt Domini. It is obvious that there was a continual tendency to alter expressions like these, and in the first age of the version it is not improbable that the continual Graecism which marks the Latin texts of D1 (Cod. Bezae), and E2 (Cod. Laud.) had a wider currency than it could maintain afterwards.

7. With regard to the African Canon of the N. T. the Old Version offers important evidence. From considerations of style and language it seems certain that the Epistle to the Hebrews, James, and 2 Peter, did not form part of the original African Version, a conclusion which falls in with that which is derived from historical testimony (comp. Westcott, General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament, p. 282 ff.). In the O. T., on the other hand, the Old Latin erred by excess and not by defect; for as the Version was made from the current copies of the LXX. it included the Apocryphal books which are commonly contained in them, and to these 2 Esdras was early added.

8. After the translation once received a definite shape in Africa, which could not have been long after the middle of the second century, it was not publicly revised. The old text was jealously guarded by ecclesiastical use, and was retained there at a time when Jerome’s Version was elsewhere almost universally received. The well-known story of the disturbance caused by the attempt of an African bishop to introduce Jerome’s “cucurbita” for the old “hedera” in the history of Jonah (August. Ep. civ. ap. Hieron. Epp., quoted by Tregelles, Introduction, p. 242) shows how carefully intentional changes were avoided. But at the same time the text suffered by the natural corruptions of copying, especially by interpolations, a form of error to which the Gospels were particularly exposed (comp. § 15). In the O. T. the version was made from the unrevised edition of the LXX. and thus from the first included many false readings of which Jerome often notices instances (e. g. Ep. cvi. ad Sun. et Fret). In Table A two texts of the Old Latin are placed for comparison with the Vulgate of Jerome.

9. The Latin translator of Irenaeus was probably contemporary with Tertullian, 5 and his renderings of the quotations from Scripture confirm the conclusions which have been already drawn as to the currency of (substantially) one Latin version. It does not appear that he had a Latin MS. before him during the execution of his work, but he was so familiar with the common translation that he reproduces continually characteristic phrases which he cannot be supposed to have derived from any other source (Lachmann, N. T. i. pp. x., xi.). Cyprian († a.d. 257) carries on the chain of testimony far through the next century; and he is followed by Lactantius, Juveneus, J. Firmicus Maternus, Hilary the deacon (Ambrosiaster), Hilary of Poitiers († a.d. 368), and Lucifer of Cagliari († a.d. 370). Ambrose and Augustine exhibit a peculiar recension of the same text, and Jerome offers some traces of it. From this date MSS. of parts of the African text have been preserved (§ 12), and it is unnecessary to trace the history of its transmission to a later time.

10. But while the earliest Latin Version was preserved generally unchanged in N. Africa, it fared differently in Italy. There the provincial rudeness of the version was necessarily more offensive, and the comparative familiarity of the leading bishops with the Greek texts made a revision at once more feasible and less startling to their congregations. Thus in the fourth century a definite ecclesiastical recension (of the Gospels at least) appears to have been made in N. Italy by reference to the Greek, which was distinguished by the name of Itala. This Augustine recommends on the ground of its close accuracy and its perspicuity (Aug. De Doctr. Christ. 15, “in ipsis interpretationibus Itala 6 caeteris praeferatur, nam est verborum tenacior cum perspicuitate sententiae”), and the text of the Gospels which he follows is marked by the latter characteristic when compared with the African. In the other books the difference cannot be traced with accuracy; and it has not yet been accurately determined whether other national recensions may not have existed (as seems certain from the evidence which the writer has collected) in Ireland (Britain), Gaul, and Spain.

11. The Itala appears to have been made in some degree with authority: other revisions were made for private use, in which such changes were introduced as suited the taste of scribe or critic. The next stage in the deterioration of the text was the intermixture of these various revisions; so that at the close of the fourth century the Gospels were in such a state as to call for that final recension which was made by Jerome. What was the nature of this confusion will be seen from the accompanying tables (B and C) more clearly than from a lengthened description.

12. The MSS. of the Old Latin which have been preserved exhibit the various forms of that version which have been already noticed. Those of the Gospels, for the reason which has been given, present the different types of text with unmistakable clearness. In the O. T. the MS. remains are too scanty to allow of a satisfactory classification.

13. It will be seen that for the chief part of the O. T., and for considerable parts of the N. T. (e. g. Apoc. Acts), the Old text rests upon early quotations (principally Tertullian, Cyprian, Lucifer of Cagliari, for the African text, Ambrose and Augustine for the Italic). These were collected by Sabatier with great diligence up to the date of his work; but more recent discoveries (e. g. of the Roman Speculum) have furnished a large store of new materials which have not yet been fully employed. (The great work of Sabatier, already often referred to, is still the standard work on the Latin Versions. His great fault is his neglect to distinguish the different types of text, African, Italic, British, Gallic; a task which yet remains to be done. The earliest work on the subject was by Flaminius Nobilius, Vetus Test. sec. LXX. Latine redditum … Romae, 1588. The new collations made by Tischendorf, Mai, Münter, Ceriani, have been noticed separately.) [See also the addition at the end of this article. — A.]

III. The Labors of Jerome. —14. It has been seen that at the close of the 4th century the Latin texts of the Bible current in the Western Church had fallen into the greatest corruption. The evil was yet greater in prospect than at the time; for the separation of the East and West, politically and ecclesiastically, was growing imminent, and the fear of the perpetuation of false and conflicting Latin copies proportionately greater. But in the crisis of danger the great scholar was raised up who probably alone for 1,500 years possessed the qualifications necessary for producing an original version of the Scriptures for the use of the Latin churches. Jerome — Eusebius Hieronymus — was born in 329 a.d. at Stridon in Dalmatia, and died at Bethlehem in 420 a.d. From his early youth he was a vigorous student, and age removed nothing from his zeal. He has been well called the Western Origen (Hody, p. 350), and if he wanted the largeness of heart and generous sympathies of the great Alexandrine, he had more chastened critical skill and closer concentration of power. After long and self-denying studies in the East and West, Jerome went to Rome a.d. 382, probably at the request of Damasus the Pope, to assist in an important synod (Ep. cviii. 6), where he seems to have been at once attached to the service of the Pope (Ep. cxxiii. 10). His active Biblical labors date from this epoch, and in examining them it will be convenient to follow the order of time, noticing (1) the Revision of the Old Latin Version of the N. T.; (2) the Revision of the Old Latin Version (from the Greek) of the O. T.; (3) the New Version of the O. T. from the Hebrew.

(1.) The Revision of the Old Latin Version of the N. T. —15. Jerome had not been long at Rome (a.d. 383) when Damasus consulted him on points of Scriptural criticism (Ep. xix. “Dilectionis tuae est ut ardenti illo strenuitatis ingenio … vivo sensu scribas”). The answers which he received (Epp. xx., xxi.) may well have encouraged him to seek for greater services; and apparently in the same year he applied to Jerome for a revision of the current Latin Version of the N. T. by the help of the Greek original. Jerome was fully sensible of the prejudices which such a work would excite among those “who thought that ignorance was holiness” (Ep. ad Marc, xxvii.), but the need of it was urgent. “There were,” he says, “almost as many forms of text as copies” (“tot sunt exemplaria pene quot codices,” Praef. in Evv.). Mistakes had been introduced “by false transcription, by clumsy corrections, and by careless interpolation” (id. ), and in the confusion which had ensued the one remedy was to go back to the original source (Graeca veritas, Graeca origo). The Gospels had naturally suffered most. Thoughtless scribes inserted additional details in the narrative from the parallels, and changed the forms of expression to those with which they had been originally familiarized (id.). Jerome therefore applied himself to these first (“haec praesens praefatiuncula pollicetur quatuor tantum Evangelia”). But his aim was to revise the Old Latin, and not to make a new version. When Augustine expressed to him his gratitude for “his translation of the Gospel” (Ep. civ. 6, “non parvas Deo gratias agimus de opere tuo quo Evangelium ex Graeco interpretatus es”), he tacitly corrected him by substituting for this phrase “the correction of the N. T.” (Ep. cxii. 20, “Si me, ut dicis, in N. T. emendatione suscipis ….”). For this purpose he collated early Greek MSS., and preserved the current rendering wherever the sense was not injured by it (“… Evangelia … codicum Graecorum emendata collatione sed veterum. Quae ne multum a lectionis Latinae consuetudine discreparent, ita calamo temperavimus (all. imperavimus) ut his tantum quae sensum videbantur mutare, correctis, reliqua manere pateremur ut fuerant;” Praef. ad Dam.). Yet although he proposed to himself this limited object, the various forms of corruption which had been introduced were, as he describes, so numerous that the difference of the Old and Revised (Hieronymian) text is throughout clear and striking. Thus in Matt. v. we have the following variations: —

|

Vetus Latina. 19 |

Vulgata nova (Hieron.). |

| 7 ipsis miserebitur Deus. | 7 ipsi misericordiam consequentur |

| 11 dixerint … | 11 dixerint … mentientes. |

| — propter justitiam. | — propter me. |

| 12 ante vos patres eorum (Luke vi. 26). | 12 ante vos. |

| 17 non veni solvere legem aut prophetas. | 17 non veni solvere. |

| 18 fiant: caelum et terra transibunt, verba autem mea non praeteribunt. | 18 fiant. |

| 22 fratri suo sine causa. | 22 fratri suo. |

| 25 es cum illo in ira. | 25 es in via cum eo (and often). |

| 29 eat in gehennam. | 29 mittatur in gehennam. |

| 37 quod autem amplius. | 37 quod autem his abundantius. |

| 41 adhuc alia duo. | 41 et alia duo. |

| 43 odies. | 43 odio habebis. |

| 44 vestros, et benedicite qui maledicent vobis et benefacite. | 44 vestros benefacite. |

|

Of these variations those in vers. 17, 44, are only partially supported by the old copies, but they illustrate the character of the interpolations from which the text suffered. In St. John, as might be expected, the variations are less frequent. The 6th chapter contains only the following: — | |

| 2 sequebatur autem. | 2 et sequebatur. |

| 21 (volebant) | 21 (voluerunt). |

| 23 (quern benedixerat Dominus (alii aliter)). | 23 (gratias agente Domino). |

| 39 haec est enim. | 39 haec est autem. |

| 39 (Patris mei). | 39 (Patris mei qui misit me). |

| 53 (manducare). | 53 (ad manducandum). |

| 66 (a patre). | 66 (a patre meo). |

| 67 ex hoc ergo. | 67 ex hoc. |

16. Some of the changes which Jerome introduced were, as will be seen, made purely on linguistic grounds, but it is impossible to ascertain on what principle he proceeded in this respect (comp. § 35). Others involved questions of interpretation (Matt. vi. 11, supersubstantialis for ἐπιούσιος). But the greater number consisted in the removal of the interpolations by which the synoptic Gospels especially were disfigured. These interpolations, unless his description is very much exaggerated, must have been far more numerous than are found in existing copies; but examples still occur which show the important service which he rendered to the Church by checking the perpetuation of apocryphal glosses: Matt. iii. 3, 15 (v. 12); (ix. 21); xx. 28; (xxiv. 36); Mark i. 3, 7, 8; iv. 19; xvi. 4; Luke (v. 10); viii. 48; ix. 43, 50; xi. 36; xii. 38; xxiii. 48; John vi. 56. As a check upon further interpolation he inserted in his text the notation of the Eusebian Canons; but it is worthy of notice that he included in his revision the famous pericope, John vii. 53-viii. 11, which is not included in that analysis.

17. The preface to Damasus speaks only of a revision of the Gospels, and a question has been raised whether Jerome really revised the remaining books of the N. T. Augustine (a.d. 403) speaks only of “the Gospel” (Ep. civ. 6, quoted above), and there is no preface to any other books, such as is elsewhere found before all Jerome’s versions or editions. But the omission is probably due to the comparatively pure state in which the text of the rest of the N. T. was preserved. Damasus had requested (Praef. ad Dam.) a revision of the whole, and when Jerome had faced the more invidious and difficult part of his work there is no reason to think that he would shrink from the completion of it. In accordance with this view he enumerates (a.d. 398) among his works “the restoration of the (Latin Version of the) N. T. to harmony with the original Greek.” (Ep. ad Lucin. lxxi. 5: “N. T. Graecae reddidi auctoritati, ut enim Veterum Librorum fides de Hebraeis voluminibus examinanda est, ita novorum Graecae (?) sermonis normam desiderat.” De Vir. Ill. cxxxv.: “N. T. Graecae fidei reddidi. Vetus juxta Hebraicam transtuli.”) It is yet more directly conclusive as to the fact of this revision, that in writing to Marcella (cir. a.d. 385) on the charges which had been brought against him for “introducing changes in the Gospels,” he quotes three passages from the Epistles in which he asserts the superiority of the present Vulgate reading to that of the Old Latin (Rom. xii. 11, Domino servientes, for tempori servientes; 1 Tim. v. 19, add. nisi sub duobus aut tribus testibus; 1 Tim. i. 15, fidelis sermo, for humanus sermo). An examination of the Vulgate text, with the quotations of ante-Hieronymian fathers and the imperfect evidence of MSS., is itself sufficient to establish the reality and character of the revision. This will be apparent from a collation of a few chapters taken from several of the later books of the N. T.; but it will also be obvious that the revision was hasty and imperfect; and in later times the line between the Hieronymian and Old texts became very indistinct. Old readings appear in MSS. of the Vulgate, and on the other hand no MS. represents a pure African text of the Acts and Epistles.

Acts i. 4-25. | |

Versio Vetus 20 | Vulg. |

| 4 cum conversaretur cum illis … quod audistis a me. | 4 convescens … quam audistis per os meum. |

| 5 tingemini. | 5 baptizabimini. |

| 6 at illi convenientes. | 6 Igitur qui convenerant. |

| 7 at ille respondens dixit. | 7 Dixit autem. |

| 8 superveniente S. S. | 8 supervenientis S. S. |

| 10 intenderent. Comp. iii. (4), 12 ; vi. 15 ; x. 4; (xiii. 9). | 10 intuerentur. |

| 13 ascenderunt in superiora. — erant habitantes. | 13 in caenaculum ascenderunt. — manebant. |

| 14 perseverantes unanimes orationi. | 14 persev. unanimiter in oratione. |

| 18 Hic igitur adquisivit. | 18 Et hic quidem possedit. |

| 21 qui convenerunt nobiscum viris. | 21 viris qui nobiscum sunt congregati. |

| 25 ire. Comp. xvii. 30. | 25 ut abiret. |

Acts xvii. 16-34. | |

| 16 circa simulacrum | 16 idololatriae deditam |

| 17 Judaeis | 17 cum Judaeis |

| 18 seminator | 18 seminiverbius |

| 22 superstitiosos | 22 superstitiosiores |

| 23 perambulans. — culturas vestras. | 23 praeteriens — simulacra vestra. |

| 26 ex uno sanguine. | 26 ex uno. |

Rom. i. 13-15. | |

| 13 Non autem arbitror. | 13 nolo autem. |

| 15 quod in me est promptus sum. | 15 quod in me promptum est. |

1 Cor. x. 4-29. | |

| 4 sequenti se (sequenti, q) (Cod. Aug. f), 21 | 4 consequente eos. |

| 6 in figuram. | 6 in figura (f), (g). |

| 7 idolorum cultores (g. corr.) efficiamur. | 7 idololatrae (idolatres, f) efficiamini (f). |

| 12 putat (g corr.). | 12 existimat (f). |

| 15 sicut prudentes, vobis dico. | 15 ut (sicut, f, g) prudentibus loquor (dico, f, g). |

| 16 quem (f, g). — communicatio (alt.) (f, g). | 16 cui. — participatio. |

| 21 participare (f, g). | 21 participes esse. |

| 29 infideli (g). | 29 (aliena); alia (f). |

2 Cor. iii. 11-18. | |

| 14 dum (quod g corr.) non revelatur (g corr.). | 14 non revelatum (f) |

| 18 de (a g) gloria in gloriam (g). | 18 a claritate in claritatem. |

Gal. iii. 14-25. | |

| 14 benedictionem (g). | 14 pollicitationem (f). |

| 15 irritum facit (irritat, g). | 15 spernit (f). |

| 25 veniente autem fide (g). | 25 At ubi fides (f). |

Phil. ii. 2-30. | |

| 2 unum (g). | 2 id ipsum (f). |

| 6 cum … constitutis (g). | 6 cum … esset (f). |

| 12 dilectissimi (g). | 12 carissimi (f). |

| 26 sollicitus (taedebatur, g). | 26 maestus (f). |

| 28 sollicitus itaque. | 28 festinantius ergo (fest. ergo, f; fest. autem, g). |

| 30 parabolatus de anima sua (g). | 30 tradens animam suam (f). |

1 Tim. iii. 1-12. | |

| 1 Humanus (g corr.). | 1 fidelis (f). |

| 2 docibilem (g). | 2 doctorem (f). |

| 4 habentem in obsequio. | 4 habentem subditos (f, g). |

| 8 turpilucros. | 8 turpe lucrum sectantes (f) (turpil. s. g). |

| 12 filios bene regentes (g corr.). | 12 qui filiis suis bene praesint (f) |

(2.) The Revision of the O.T. from the LXX. —18. About the same time (cir. a.d. 383) at which he was engaged on the revision of the N. T., Jerome undertook also a first revision of the Psalter. This he made by the help of the Greek, but the work was not very complete or careful, and the words in which he describes it may, perhaps, be extended without injustice to the revision of the later books of the N. T.: “Psalterium Romae … emendaram et juxta LXX. interpretes, licet cursim magna illud ex parte correxeram” (Praef. in Lib. Ps.). This revision obtained the name of the Roman Psalter, probably because it was made for the use of the Roman Church at the request of Damasus, where it was retained till the pontificate of Pius V. (a.d. 1566), who introduced the Gallican Psalter generally, though the Roman Psalter was still retained in three Italian churches (Hody, p. 383, “in una Romae Vaticana ecclesia, et extra urbem in Mediolanensi et in ecclesia S. Marci, Venetiis”). In a short time “the old error prevailed over the new correction,” and at the urgent request of Paula and Eustochium Jerome commenced a new and more thorough revision (Gallican Psalter). 22 The exact date at which this was made is not known, but it may be fixed with great probability very shortly after a.d. 387, when he retired to Bethlehem, and certainly before 391, when he had begun his new translations from the Hebrew. In the new revision Jerome attempted to represent as far as possible, by the help of the Greek Versions, the real reading of the Hebrew. With this view he adopted the notation of Origen [compare Praef. in Gen., etc.], and thus indicated all the additions and omissions of the LXX. text reproduced in the Latin. The additions were marked by an obelus (÷); the omissions, which he supplied, by an asterisk (*). The omitted passages he supplied by a version of the Greek of Theodotion, and not directly from the Hebrew (“unusquisque ... ubicunque viderit virgulam praecedentem (÷) ab ea usque ad duo puncta (″) quae impressimus, sciat in LXX. interpretibus plus haberi. Ubi autem stellae (*) similitudinem perspexerit, de Hebraeis voluminibus additum noverit, aeque usque ad duo puncta, juxta Theodotionis dumtaxat editionem, qui simplicitate sermonis a LXX. interpretibus non discordat” Praef. ad Ps.; compare Praeff. in Job, Paralip. Libr. Solom. juxta LXX., Intt., Ep. cvi. ad Sun. et Fret.). This new edition soon obtained a wide popularity. Gregory of Tours is said to have introduced it from Rome into the public services in France, and from this it obtained the name of the Gallican Psalter. The comparison of one or two passages will show the extent and nature of the corrections which Jerome introduced into this second work, as compared with the Roman Psalter. (See Table D.)

How far he thought change really necessary will appear from a comparison of a few verses of his translation from the Hebrew with the earlier revised Septuagintal translations. (See Table E.)

Numerous MSS. remain which contain the Latin Psalter in two or more forms. Thus Bibl. Bodl. Laud. 35 (Saec. x. ?) contains a triple Psalter, Gallican, Roman, and Hebrew: Coll. C. C. Oxon. xii. (Saec. xv.) Gallican, Roman, Hebrew: Id. x. (Saec. xiv.) Gallican, Hebrew, Hebr. text with interlinear Latin: Brit. Mus. Harl. 634, a double Psalter, Gallican and Hebrew: Brit. Mus. Arund. 155 (Saec. xi.) a Roman Psalter with Gallican corrections: Coll. SS. Trin. Cambr., R. 17, 1, a triple Psalter, Hebrew, Gallican, Roman (Saec. xii.): Id. R. 8, 6, a triple Psalter, the Hebrew text, with a peculiar interlinear Latin Version, Jerome’s Hebrew, Gallican. An example of the unrevised Latin, which, indeed, is not very satisfactorily distinguished from the Roman, is found with an Anglo-Saxon interlinear version, Univ. Libr. Cambr. Ff. i. 23 (Saec. xi.). H. Stephens published a “Quincuplex Psalterium, Gallicum, Rhomaicum, Hebraicum, Vetus, Conciliatum … Paris, 1513,” but he does not mention the MSS. from which he derived his texts.

19. From the second (Gallican) revision of the Psalms Jerome appears to have proceeded to a revision of the other books of the O. T., restoring all, by the help of the Greek, to a general conformity with the Hebrew. In the preface to the Revision of Job, he notices the opposition which he had met with, and contrasts indignantly his own labors with the more mechanical occupations of monks which excited no reproaches (“Si aut fiscellam junco texerem aut palmarum folia complicarem … nullus morderet, nemo reprehenderet. Nunc autem … corrector vitiorum falsarius vocor”). Similar complaints, but less strongly expressed, occur in the preface to the books of Chronicles, in which he had recourse to the Hebrew as well as to the Greek, in order to correct the innumerable errors in the names by which both texts were deformed. In the preface to the three books of Solomon (Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Canticles) he notices no attacks, but excuses himself for neglecting to revise Ecclesiasticus and Wisdom, on the ground that “he wished only to amend the Canonical Scriptures” (“tantummodo Canonicas Scripturas vobis emendare desiderans”). No other prefaces remain, and the revised texts of the Psalter and Job have alone been preserved; but there is no reason to doubt that Jerome carried out his design of revising all the “Canonical Scriptures” (comp. Ep. cxii. ad August. (cir. a.d. 404), “Quod autem in aliis quaeris epistolis: cur prior mea in libris Canonicis interpretatio asteriscos habeat et virgulas praenotatas …”). He speaks of this work as a whole in several places (e. g. adv. Ruf. ii. 24, “Egone contra LXX. interpretes aliquid sum locutus, quos ante annos plurimos diligentissime emendatos meae linguae studiosis dedi … ?” Comp. Id. iii. 25; Ep. lxxi. ad Lucin., “Septuaginta interpretum editionem et te habere non dubito, et ante annos plurimos (he is writing a.d. 398) diligentissime emendatam studiosis tradidi”), and distinctly represents it as a Latin Version of Origen’s Hexaplar text (Ep. cvi. ad Sun. et Fret., “Ea autem quae habetur in Ἑξαπλοῖς et quam non vertimus”), if, indeed, the reference is not to be confined to the Psalter, which was the immediate subject of discussion. But though it seems certain that the revision was made, there is very great difficulty in tracing its history, and it is remarkable that no allusion to the revision occurs in the preface to the new translation of the Pentateuch, Joshua (Judges, Ruth), Kings, the Prophets, in which Jerome touches more or less plainly on the difficulties of his task, while he does refer to his former labors on Job, the Psalter, and the books of Solomon in the parallel prefaces to those books, and also in his Apology against Rufinus (ii. 27, 29, 30, 31). It has, indeed, been supposed (Vallarsi, Praef. in Hier. x.) that these six books only were published by Jerome himself. The remainder may have been put into circulation surreptitiously. But this supposition is not without difficulties. Augustine, writing to Jerome (cir. a.d. 405), earnestly begs for a copy of the revision from the LXX., of the publication of which he was then only lately aware (Ep. xcvi. 34, “Deinde nobis mittas, obsecro, interpretationem tuam de Septuaginta, quam te edidisse nesciebam;” comp. § 34). It does not appear whether the request was granted or not, but at a much later period (cir. a.d. 416) Jerome says that he cannot furnish him with “a copy of the LXX. (i. e. the Latin version of it) furnished with asterisks and obeli, as he had lost the chief part of his former labor by some person’s treachery” (Ep. cxxxiv., “Pleraque prioris laboris fraude cujusdam amisimus”). However this may have been, Jerome could not have spent more than four (or five) years on the work, and that too in the midst of other labors, for in 491 he was already engaged on the versions from the Hebrew which constitute his great claim on the lasting gratitude of the Church.

(3.) The Translation of the O.T. from the Hebrew. — 20. Jerome commenced the study of Hebrew when he was already advanced in middle life (cir. a.d. 374), thinking that the difficulties of the language, as he quaintly paints them, would serve to subdue the temptations of passion to which he was exposed (Ep. cxxv. § 12; comp. Praef. in Dan.). From this time he continued the study with unabated zeal, and availed himself of every help to perfect his knowledge of the language. His first teacher had been a Jewish convert; but afterwards he did not scruple to seek the instruction of Jews, whose services he secured with great difficulty and expense. This excessive zeal (as it seemed) exposed him to the misrepresentations of his enemies, and Rufinus indulges in a silly pun on the name of one of his teachers, with the intention of showing that his work was not “supported by the authority of the Church, but only of a second Barabbas” (Ruf. Apol. ii. 12; Hieron. Apol. i. 13; comp. Ep. lxxxiv. § 3, and Praef. in Paral.). Jerome, however, was not deterred by opposition from pursuing his object, and it were only to be wished that he had surpassed his critics as much in generous courtesy as he did in honest labor. He soon turned his knowledge of Hebrew to use. In some of his earliest critical letters he examines the force of Hebrew words (Epp. xviii., xx., a.d. 381, 383); and in a.d. 384, he had been engaged for some time in comparing the version of Aquila with Hebrew MSS. (Ep. xxxii. § 1), which a Jew had succeeded in obtaining for him from the synagogue (Ep. xxxvi. § 1). After retiring to Bethlehem, he appears to have devoted himself with renewed ardor to the study of Hebrew, and he published several works on the subject (cir. a.d. 389; Quaest. Hebr. in Gen. etc.). These essays served as a prelude to his New Version, which he now commenced. This version was not undertaken with any ecclesiastical sanction, as the revision of the Gospels was, but at the urgent request of private friends, or from his own sense of the imperious necessity of the work. Its history is told in the main in the prefaces to the several installments which were successively published. The Books of Samuel and Kings were issued first, and to these he prefixed the famous Prologus galeatus, addressed to Paula and Eustochium, in which he gives an account of the Hebrew Canon. It is impossible to determine why he selected these books for his experiment, for it does not appear that he was requested by any one to do so. The work itself was executed with the greatest care. Jerome speaks of the translation as the result of constant revision (Prol. Gal., “Lege ergo primum Samuel et Malachim meum: meum, inquam, meum. Quidquid enim crebrius vertendo et emendando sollicitius et didicimus et tenemus nostrum est”). At the time when this was published (cir. a.d. 391, 392) other books seem to have been already translated (Prol. Gal., “omnibus libris quos de Hebraeo vertimus”); and in 393 the sixteen prophets 23 were in circulation, and Job had lately been put into the hands of his most intimate friends (Ep. xlix. ad Pammach.). Indeed, it would appear that already in 392 he had in some sense completed a version of the O. T. (De Vir. Ill. cxxxv., “Vetus juxta Hebraicum transtuli.” This treatise was written in that year); 24 but many books were not completed and published till some years afterwards. The next books which he put into circulation, yet with the provision that they should be confined to friends (Praef. in Ezr.), were Ezra and Nehemiah, which he translated at the request of Dominica and Rogatianus, who had urged him to the task for three years. This was probably in the year 394 (Vit. Hieron. xxi. 4), for in the preface he alludes to his intention of discussing a question which he treats in Ep. lvii., written in 395 (De optimo Gen. interpret.). In the preface to the Chronicles (addressed to Chromatius), he alludes to the same epistle as “lately written,” and these books may therefore be set down to that year. The three books of Solomon followed in 398, 25 having been “the work of three days” when he had just recovered from a severe illness, which he suffered in that year (Praef. “Itaque longa aegrotatione fractus … tridui opus nomini vestro [Chromatio et Heliodoro] consecravi.” Comp. Ep. lxxiii. 10). The Octateuch now alone remained (Ep. lxxi. 5, i. e. Pentateuch, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, and Esther, Praef. in Jos.). Of this the Pentateuch (inscribed to Desiderius) was published first, but it is uncertain in what year. The preface, however, is not quoted in the Apology against Rufinus (a.d. 400), as those of all the other books which were then published, and it may therefore be set down to a later date (Hody, p. 357). The remaining books were completed at the request of Eustochium, shortly after the death of Paula, a.d. 404 (Praef. in Jos.). Thus the whole translation was spread over a period of about fourteen years, from the sixtieth to the seventy-sixth year of Jerome’s life. But still parts of it were finished in great haste (e. g. the books of Solomon). A single day was sufficient for the translation of Tobit (Praef. in Tob.); and “one short effort” (una lucubratiuncula) for the translation of Judith. Thus there are errors in the work which a more careful revision might have removed, and Jerome himself in many places gives renderings which he prefers to those which he had adopted, and admits from time to time that he had fallen into error (Hody, p. 362). Yet such defects are trifling when compared with what he accomplished successfully. The work remained for eight centuries the bulwark of western Christianity; and as a monument of ancient linguistic power the translation of the O. T. stands unrivaled and unique. It was at least a direct rendering of the original, and not the version of a version. The Septuagintal tradition was at length set aside, and a few passages will show the extent and character of the differences by which the new translation was distinguished from the Old Latin which it superseded.

IV. The History of Jerome’s Translation to the Invention of Printing. — 21. The critical labors of Jerome were received, as such labors always are received by the multitude, with a loud outcry of reproach. He was accused of disturbing the repose of the Church, and shaking the foundations of faith. Acknowledged errors, as he complains, were looked upon as hallowed by ancient usage (Praef. in Job ii.); and few had the wisdom or candor to acknowledge the importance of seeking for the purest possible text of Holy Scripture. Even Augustine was carried away by the popular prejudice, and endeavored to discourage Jerome from the task of a new translation (Ep. civ.), which seemed to him to be dangerous and almost profane. Jerome, indeed, did little to smooth the way for the reception of his work. The violence and bitterness of his language is more like that of the rival scholars of the 16th century than of a Christian Father; and there are few more touching instances of humility than that of the young Augustine bending himself in entire submission before the contemptuous and impatient reproof of the veteran scholar (Ep. cxii. s. f.). But even Augustine could not overcome the force of early habit. To the last he remained faithful to the Italic text which he had first used; and while he notices in his Retractationes several faulty readings which he had formerly embraced, he shows no tendency to substitute generally the New Version for the Old. 26 In such cases time is the great reformer. Clamor based upon ignorance soon dies away; and the new translation gradually came into use equally with the old, and at length supplanted it. In the 5th century it was adopted in Gaul by Eucherius of Lyons, Vincent of Lerins, Sedulius and Claudianus Mamertus (Hody, p. 398); but the Old Latin was still retained in Africa and Britain (ibid.). In the 6th century the use of Jerome’s Version was universal among scholars except in Africa, where the other still lingered (Junilius); and at the close of it Gregory the Great, while commenting on Jerome’s Version, acknowledged that it was admitted equally with the Old by the Apostolic See (Praef. in Job ad Leandrum), “Novam translationem dissero, sed ut comprobationis causa exigit, nunc Novam, nunc Veterem, per testimonia assumo: ut quia sedes Apostolica (cui auctore Deo praesideo) utraque utitur mei quoque labor studii ex utraque fulciatur.” But the Old Version was not authoritatively displaced, though the custom of the Roman Church prevailed also in the other churches of the West. Thus Isidore of Seville (De Offic. Eccles. i. 12), after affirming the inspiration of the LXX., goes on to recommend the Version of Jerome, “which,” he says, “is used universally, as being more truthful in substance and more perspicuous in language.” “[Hieronymi] editione generaliter omnes ecclesiae usquequaque utuntur, pro eo quod veracior sit in sententiis et clarior in verbis:” (Hody, p. 402). In the 7th century the traces of the Old Version grow rare. Julianus of Toledo (a.d. 676) affirms with a special polemical purpose the authority of the LXX., and so of the Old Latin; but still he himself follows Jerome when not influenced by the requirements of controversy (Hody, pp. 405, 406). In the 8th century Bede speaks of Jerome’s Version as “our edition” (Hody, p. 408); and from this time it is needless to trace its history, though the Old Latin was not wholly forgotten. 27 Yet throughout, the New Version made its way without any direct ecclesiastical authority. It was adopted in the different churches gradually, or at least without any formal command. (Compare Hody, p. 411 ff. for detailed quotations.)

22. But the Latin Bible which thus passed gradually into use under the name of Jerome was a strangely composite work. The books of the O. T., with one exception, were certainly taken from his version from the Hebrew; but this had not only been variously corrupted, but was itself in many particulars (especially in the Pentateuch) at variance with his later judgment. Long use, however, made it impossible to substitute his Psalter from the Hebrew for the Gallican Psalter; and thus this book was retained from the Old Version, as Jerome had corrected it from the LXX. Of the Apocryphal books Jerome hastily revised or translated two only, Judith and Tobit. The remainder were retained from the Old Version against his judgment; and the Apocryphal additions to Daniel and Esther, which he had carefullv marked as apocryphal in his own version, were treated as integral parts of the books. A few MSS. of the Bible faithfully preserved the “Hebrew Canon,” but the great mass, according to the general custom of copyists to omit nothing, included everything which had held a place in the Old Latin. In the N. T. the only important addition which was frequently interpolated was the apocryphal Epistle to the Laodiceans. The text of the Gospels was in the main Jerome’s revised edition; that of the remaining books his very incomplete revision of the Old Latin. Thus the present Vulgate contains elements which belong to every period and form of the Latin Version — (1.) Unrevised Old Latin: Wisdom, Ecclus., 1, 2 Macc., Baruch. (2.) Old Latin revised from the LXX.: Psalter. (3.) Jerome’s free translation from the original text: Judith, Tobit. (4.) Jerome’s translation from the Original: O. T. except Psalter. (5.) Old Latin revised from Greek MSS.: Gospels. (6.) Old Latin cursorily revised : the remainder of N. T.

The Revision of Alcuin. — 23. Meanwhile the text of the different parts of the Latin Bible was rapidly deteriorating. The simultaneous use of the Old and New versions necessarily led to great corruptions of both texts. Mixed texts were formed according to the taste or judgment of scribes, and the confusion was further increased by the changes which were sometimes introduced by those who had some knowledge of Greek. 28 From this cause scarcely any Anglo-Saxon Vulgate MS. of the 8th or 9th centuries which the writer has examined is wholly free from an admixture of old readings. Several remarkable examples are noticed below (§ 32); and in rare instances it is difficult to decide whether the text is not rather a revised Vetus than a corrupted Vulgata nova (e. g. Brit. Mus. Reg. i. E. vi.; Addit. 5,463). As early as the 6th century, Cassiodorus attempted a partial revision of the text (Psalter, Prophets, Epistles) by a collation of old MSS. But private labor was unable to check the growing corruption; and in the 8th century this had arrived at such a height, that it attracted the attention of Charlemagne. Charlemagne at once sought a remedy, and entrusted to Alcuin (cir. a.d. 802) the task of revising the Latin text for public use. This Alcuin appears to have done simply by the use of MSS. of the Vulgate, and not by reference to the original texts (Porson, Letter vi. to Travis, p. 145). The passages which are adduced by Hody to prove his familiarity with Hebrew, are in fact only quotations from Jerome, and he certainly left the text unaltered, at least in one place where Jerome points out its inaccuracy (Gen. xxv. 8). 29 The patronage of Charlemagne gave a wide currency to the revision of Alcuin, and several MSS. remain which claim to date immediately from his time. 30 According to a very remarkable statement, Charlemagne was more than a patron of sacred criticism, and himself devoted the last year of his life to the correction of the Gospels “with the help of Greeks and Syrians” (Van Ess, p. 159, quoting Theganus, Script. Hist. Franc., ii. 277). 31

24. However this may be, it is probable that Aicuin’s revision contributed much towards preserving a good Vulgate text. The best MSS. of his recension do not differ widely from the pure Hieronymian text, and his authority must have done much to check the spread of the interpolations which reappear afterwards, and which were derived from the intermixture of the Old and New Versions. Examples of readings which seem to be due to him occur: Deut. i. 9, add. solitudinem; venissemus, for -etis; id. 4, ascendimus, for ascendemus; ii. 24, in manu tua, for in manus tuas; iv. 33, vidisti, for vixisti; vi. 13, ipsi, add. soli; xv. 9, oculos, om. tuos; xvii. 20, filius, for filii; xx. 6, add. venient; xxvi. 16, at, for et. But the new revision was gradually deformed, though later attempts at correction were made by Lanfranc of Canterbury (a.d. 1089, Hody, p. 416), Card. Nicolaus (a.d. 1150), and the Cistercian Abbot Stephanus (cir. a.d. 1150). In the 13th century Correctoria were drawn up, especially in France, in which varieties of reading were discussed; 32 and Roger Bacon complains loudly of the confusion which was introduced into the “Common, that is the Parisian copy,” and quotes a false reading from Mark viii. 38, where the correctors had substituted confessus for confusus (Hody, pp. 419 ff.). Little more was done for the text of the Vulgate till the invention of printing; and the name of Laurentius Valla (cir. 1450) alone deserves mention, as of one who devoted the highest powers to the criticism of Holy Scripture, at a time when such studies were little esteemed. 33

V. The History of the Printed Text. — 25. It was a noble omen for the future progress of printing that the first book which issued from the press was the Bible; and the splendid pages of the Mazarin Vulgate (Mainz, Gutenburg and Fust) stand yet unsurpassed by the latest efforts of typography. This work is referred to about the year 1455, and presents the common text of the 15th century. Other editions followed in rapid succession (the first with a date, Mainz, 1462, Fust and Schoiffer), but they offer nothing of critical interest. The first collection of various readings appears in a Paris edition of 1504, and others followed at Venice and Lyons in 1511, 1513; but Cardinal Ximenes (1502-1517) was the first who seriously revised the Latin text (“… contulimus cum quamplurimis exemplaribus venerandae vetustatis; sed his maxime, quae in publica Complutensis nostrae Universitatis bibliotheca reconduntur, quae supra octingentesimum abhinc annum litteris Gothicis conscripta, ea sunt sinceritate ut nec apicis lapsus possit in eis deprehendi,” Praef.), 34 to which he assigned the middle place of honor in his Polyglott between the Hebrew and Greek texts. The Complutensian text is said to be more correct than those which preceded it, but still it is very far from being pure. This was followed in 1528 (2d edition 1532) by an edition of R. Stephens, who had bestowed great pains upon the work, consulting three MSS. of high character and the earlier editions, but as yet the best materials were not open for use. About the same time various attempts were made to correct the Latin from the original texts (Erasmus, 1516; 35 Pagninus, 1518-28; Card. Cajetanus; Steuchius, 1529; Clarius, 1542), or even to make a new Latin version (Jo. Campensis, 1533). A more important edition of R. Stephens followed in 1540, in which he made use of twenty MSS. and introduced considerable alterations into his former text. In 1541 another edition was published by Jo. Benedictus at Paris, which was based on the collation of MSS. and editions, and was often reprinted afterwards. Vercellone speaks much more highly of the Biblia Ordinaria, with glosses, etc, published at Lyons, 1545, as giving readings in accordance with the oldest MSS., though the sources from which they are derived are not given (Variea Lect. xcix.). The course of controversy in the 16th century exaggerated the importance of the differences in the text aud interpretation of the Vulgate, and the confusion called for some remedy. An authorized edition became a necessity for the Romish Church, and, however gravely later theologians may have erred in explaining the policy or intentions of the Tridentine Fathers on this point, there can be no doubt that (setting aside all reference to the original texts) the principle of their decision — the preference, that is, of the oldest Latin text to any later Latin version — was substantially right. 36

The Sixtine and Clementine Vulgates. — 26. The first session of the Council of Trent was held on Dec. 13th, 1545. After some preliminary arrangements the Nicene Creed was formally promulgated as the foundation of the Christian faith on Feb. 4th, 1546, and then the Council proceeded to the question of the authority, text, and interpretation of Holy Scripture. A committee was appointed to report upon the subject, which held private meetings from Feb. 20th to March 17th. Considerable varieties of opinion existed as to the relative value of the original and Latin texts, and the final decree was intended to serve as a compromise. 37 This was made on April 8th, 1546, and consisted of two parts, the first of which contains the list of the canonical books, with the usual anathema on those who refuse to receive it; while the second, “On the Edition and Use of the Sacred Books,” contains no anathema, so that its contents are not articles of faith. 38 The wording of the decree itself contains several marks of the controversy from which it arose, and admits of a far more liberal construction than later glosses have affixed to it. In affirming the authority of the ‘Old Vulgate’ it contains no estimate of the value of the original texts. The question decided is simply the relative merits of the current Latin versions (“si ex omnibus Latinis versionibus quae circumferuntur …”), and this only in reference to public exercises. The object contemplated is the advantage (utilitas) of the Church, and not anything essential to its constitution. It was further enacted, as a check to the license of printers, that “Holy Scripture, but especially the old and common (Vulgate) edition (evidently without excluding the original texts), should be printed as correctly as possible.” In spite, however, of the comparative caution of the decree, and the interpretation which was affixed to it by the highest authorities, it was received with little favor, and the want of a standard text of the Vulgate practically left the question as unsettled as before. The decree itself was made by men little fitted to anticipate the difficulties of textual criticism, but afterwards these were found to be so great that for some time it seemed that no authorized edition would appear. The theologians of Belgium did something to meet the want. In 1547 the first edition of Hentenius appeared at Louvain, which had very considerable influence upon later copies. It was based upon the collation of Latin MSS. and the Stephanic edition of 1540. In the Antwerp Polyglott of 1568-1572 the Vulgate was borrowed from the Complutensian (Vercellone, Var. Lect. ci.); but in the Antwerp edition of the Vulgate of 1573-74 the text of Hentenius was adopted with copious additions of readings by Lucas Brugensis. This last was designed as the preparation and temporary substitute for the Papal edition: indeed it may be questioned whether it was not put forth as the “correct edition required by the Tridentine decree” (comp. Lucas Brug. ap. Vercellone, cii.). But a Papal board was already engaged, however desultorily, upon the work of revision. The earliest trace of an attempt to realize the recommendations of the Council is found fifteen years after it was made. In 1561 Paulus Manutius (son of Aldus Manutius) was invited to Rome to superintend the printing of Latin and Greek Bibles (Vercellone, Var. Lect. etc., i. Prol. xix. n.). During that year and the next several scholars (with Sirletus at their head) were engaged in the revision of the text. In the pontificate of Pius V. the work was continued, and Sirletus still took a chief part in it (1569, 1570, Vercellone, l. c. xx. n.), but it was currently reported that the difficulties of publishing an authoritative edition were insuperable. Nothing further was done towards the revision of the Vulgate under Gregory XIII., but preparations were made for an edition of the LXX. This appeared in 1587, in the second year of the pontificate of Sixtus V., who had been one of the chief promoters of the work. After the publication of the LXX., Sixtus immediately devoted himself to the production of an edition of the Vulgate. He was himself a scholar, and his imperious genius led him to face a task from which others had shrunk. “He had felt,” he says, “from his first accession to the papal throne (1585), great grief, or even indignation (indigne ferentes), that the Tridentine decree was still unsatisfied;” and a board was appointed, under the presidency of Card. Carafa, to arrange the materials and offer suggestions for an edition. Sixtus himself revised the text, rejecting or confirming the suggestions of the board by his absolute judgment; and when the work was printed he examined the sheets with the utmost care, and corrected the errors with his own hand. 39 The edition appeared in 1590, with the famous constitution Æternus ille (dated March 1st, 1589) prefixed, in which Sixtus affirmed with characteristic decision the plenary authority of the edition for all future time. “By the fullness of Apostolical power” (such are his words) “we decree and declare that this edition … approved by the authority delivered to us by the Lord, is to be received and held as true, lawful, authentic, and unquestioned, in all public and private discussion, reading, preaching, and explanation.” 40 He further forbade expressly the publication of various readings in copies of the Vulgate, and pronounced that all readings in other editions and MSS. which vary from those of the revised text “are to have no credit or authority for the future” (ea in iis quae huic nostrae editioni non consenserint, nullam in posterum fidem, nullamque auctoritatem habitura esse decernimus). It was also enacted that the new revision should be introduced into all missals and service-books; and the greater excommunication was threatened against all who in any way contravened the constitution. Had the life of Sixtus been prolonged, there is no doubt but that his iron will would have enforced the changes which he thus peremptorily proclaimed; but he died in Aug. 1590, and those whom he had alarmed or offended took immediate measures to hinder the execution of his designs. Nor was this without good reason. He had changed the readings of those whom he had employed to report upon the text with the most arbitrary and unskillful hand; and it was scarcely an exaggeration to say that his precipitate “self-reliance had brought the Church into the most serious peril.” 41 During the brief pontificate of Urban VII. nothing could be done; but the reaction was not long delayed.

On the accession of Gregory XIV. some went so far as to propose that the edition of Sixtus should be absolutely prohibited; but Bellarmin suggested a middle course. He proposed that the erroneous alterations of the text which had been made in it (“quae male mutata erant”) “should be corrected with all possible speed and the Bible reprinted under the name of Sixtus, with a prefatory note to the effect that errors (aliqua errata) had crept into the former edition by the carelessness of the printers.” 42 This pious fraud, or rather daring falsehood, 43 for it can be called by no other name, found favor with those in power. A commission was appointed to revise the Sixtine text, under the presidency of the Cardinal Colonna (Columna). At first the commissioners made but slow progress, and it seemed likely that a year would elapse before the revision was completed (Ungarelli, in Vercellone, Proleg. lviii.). The mode of proceedings was therefore changed, and the commission moved to Zagarolo, the country seat of Colonna; and, if we may believe the inscription which still commemorates the event, and the current report of the time, the work was completed in nineteen days. But even if it can be shown that the work extended over six months, it is obvious that there was no time for the examination of new authorities, but only for making a rapid revision with the help of the materials already collected. The task was hardly finished when Gregory died (Oct. 1591), and the publication of the revised text was again delayed. His successor, Innocent IX., died within the same year, and at the beginning of 1592 Clement VIII. was raised to the popedom. Clement entrusted the final revision of the text to Toletus, and the whole was printed by Aldus Manutius (the grandson) before the end of 1592. The Preface, which is moulded upon that of Sixtus, was written by Bellarmin, and is favorably distinguished from that of Sixtus by its temperance and even modesty. The text, it is said, had been prepared with the greatest care, and though not absolutely perfect was at least (what is no idle boast) more correct than that of any former edition. Some readings indeed, it is allowed, had, though wrong, been left unchanged, to avoid popular offense. 44 But yet even here Bellarmin did not scruple to repeat the fiction of the intention of Sixtus to recall his edition, which still disgraces the front of the Roman Vulgate by an apology no less needless than untrue. 45 Another edition followed in 1593, and a third in 1598, with a triple list of errata, one for each of the three editions. Other editions were afterwards published at Rome (comp. Vercellone, civ.), but with these corrections the history of the authorized text properly concludes.

27. The respective merits of the Sixtine and Clementine editions have been often debated. In point of mechanical accuracy, the Sixtine seems to be clearly superior (Van Ess, 365 ff.), but Van Ess has allowed himself to be misled in the estimate which he gives of the critical value of the Sixtine readings. The collections lately published by Vercellone 46 place in the clearest light the strange and uncritical mode in which Sixtus dealt with the evidence and results submitted to him. The recommendations of the Sixtine correctors are marked by singular wisdom and critical tact, and in almost every case where Sixtus departs from them he is in error. This will be evident from a collation of the readings in a few chapters as given by Vercellone. Thus in the first four chapters of Genesis the Sixtine correctors are right against Sixtus: i. 2, 27, 31; ii. 18, 20; iii. 1, 11, 12, 17, 21, 22; iv. 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 15, 16, 19; and on the other hand Sixtus is right against the correctors in i. 15. The Gregorian correctors, therefore (whose results are given in the Clementine edition), in the main simply restored readings adopted by the Sixtine board and rejected by Sixtus. In the book of Deuteronomy the Clementine edition follows the Sixtine correctors where it differs from the Sixtine edition: i. 4, 19, 31; ii. 21; iv. 6, 22, 28, 30, 33, 39; v. 24; vi. 4; viii. 1; ix. 9; x. 3; xi. 3; xii. 11, 12, 15, &c.; and every change (except probably vi. 4; xii. 11, 12) is right; while on the other hand in the same chapters there are, as far as I have observed, only two instances of variation without the authority of the Sixtine correctors (xi. 10, 32). But in point of fact the Clementine edition errs by excess of caution. Within the same limits it follows Sixtus against the correctors wrongly in ii. 33; iii. 10, 12, 13, 16, 19, 20; iv. 10, 11, 28, 42; vi. 3; xi. 28; and in the whole book admits in the following passages arbitrary changes of Sixtus: iv. 10; v. 24; vi. 13; xii. 15, 32; xviii. 10, 11; xxix. 23. 47 In the N. T., as the report of the Sixtine correctors has not yet been published, it is impossible to say how far the same law holds good; but the following comparison of the variations of the two editions in continuous passages of the Gospels and Epistles will show that the Clementine, though not a pure text, is yet very far purer than the Sixtine, which often gives Old Latin readings, and sometimes appears to depend simply on patristic authority 48 (i. e. pp. ll.): —

| Sixtine. | Clementine. | |

| Matt. i. 23, | vocabitur (pp. ll.). | — vocabunt |

| ii. 5, | Juda (gat. mm. etc.). | — Judæ. |

| 13, | surge, accipe (?). | — surge et accipe. |

| iii. 2, | appropinquabit (iv. 17), (MSS. Gallic. pp. ll). | — appropinquavit. |

| 3, | de quo dictum est (tol. it.). | — qui dictus est. |

| 10, | arboris (Tert.). | — arborum. |

| iv. 6, | ut .... tollant (it.). | — et .... tollent. |

| 7, | Jesus rursum. | — Jesus : Rursum. |

| 15, | Galilææ (it. am. etc.). | — Galilæa. |

| 16, | ambulabat (?). | — sedebat. |

| v. 11, | vobis homines (gat. mm. etc.). | — vobis. |

| 30, | abscinde (?). | — abscide. |

| 40, | in judicio (it.). | — judicio. |

| vi. 7, | eth, faciunt (it.). | — ethnici. |

| 30, | enim (it.). | — autem. |

| vii. 1, | et non judicabimini, nolite condemnare et non condemnabimini (?). | — ut non judicemini. |

| 4, | sine, frater (it. pp. ll.). | — sine. |

| 23, | a me omnes (it. pp. ll.). | — a me. |

| 25, | supra (pp. ll. tol. etc.). | — super. |

| 29, | scribæ (it.). | — scribæ eorum. |

| viii. 9, | alio (it. am. etc.). | — alii. |

| 12, | ubi (pp. ll.). | — ibi. |

| 18, | jussit discipulos (it.). | — jussit. |

| 20, | caput suum (it. tol.). | — caput. |

| 28, | venisset Jesus (it.). | — venisset. |

| 32, | magno impetu (it.). | — impetu. |

| 33, | hæc omnia (?). | — omnia. |

| 34, | rogabant eum ut Jesus (?). | — rogabant ut. |

| Ephes. i. 15, | in Christo J (pp. ll. Bodl.). | — in Domino J. |

| 21, | dominationem (?). | — et dominationem. |

| ii. 1, | vos convivificavit (pp. ll.). | — vos. |

| 11, | vos eratis (pp. ll. Bodl. etc.). | — vos. |

| —, | dicebamini (pp. ll.). | — dicimini. |

| 12, | qui (pp. ll. Bodl. etc). | — quod. |

| 22, | Spiritu Sancto (pp. ll. Sang. etc.). | — Spiritu. |

| iii. 8, | mihi enim (pp. ll.). | — mihi. |

| 16, | virtutem (it.). | — virtute. |

| —, | in interiore homine (pp. ll. Bodl.). | — in interiorem hominem. |

| iv. 22, | deponite (it.). | — deponere. |

| 30, | in die (pp. ll. Bodl. etc.) | — in diem. |

| v. 26, | mundans eam (pp. ll.). | — mundans. |

| 27, | in gloriosam (?). | — gloriosam. |

| vi. 15, | in præparationem (it.) | — in præparatione. |

| 20, | in catena ista (it.?). | — in catena ita. |

| (Some of the readings of Bodl. (§ 13, (3) s2) are added. It. is used, as is commonly done, for the old texts generally; and the notation of the MSS. is that usually followed.) | ||

28. While the Clementine edition was still recent some thoughts seem to have been entertained of revising it. Lucas Brugensis made important collections for this purpose, but the practical difficulties were found to be too great, and the study of various readings was reserved for scholars (Bellarmin. ad Lucam Brug. 1606). In the next generation use and controversy gave a sanctity to the authorized text. Many, especially in Spain, pronounced it to have a value superior to the originals, and to be inspired in every detail (comp. Van Ess, 401, 402; Hody, III. ii. 15); but it is useless to dwell on the history of such extravagancies, from which the Jesuits at least, following their great champion Bellarmin, wisely kept aloof. It was a more serious matter that the universal acceptance of the papal text checked the critical study of the materials on which it was professedly based. At length, however, in 1706, Martianay published a new, and in the main better text, chiefly from original MSS., in his edition of Jerome. Vallarsi added fresh collations in his revised issue of Martianay’s work, but in both cases the collations are imperfect, and it is impossible to determine with accuracy on what MS. authority the text which is given depends. Sabatier, though professing only to deal with the Old Latin, published important materials for the criticism of Jerome’s Version, and gave at length the readings of Lucas Brugensis (1743). More than a century elapsed before anything more of importance was done for the Text of the Latin version of the O. T., when at length the fortunate discovery of the original revision of the Sixtine correctors again directed the attention of Roman scholars to their authorized text. The first-fruits of their labors are given in the volume of Vercellone already often quoted, which has thrown more light upon the history and criticism of the Vulgate than any previous work. There are some defects in the arrangement of the materials, and it is unfortunate that the editor has not added either the authorized or corrected text; but still the work is such that every student of the Latin text must wait anxiously for its completion.

29. The neglect of the Latin text of the O. T. is but a consequence of the general neglect of the criticism of the Hebrew text. In the N. T. far more has been done for the correction of the Vulgate, though even here no critical edition has yet been published. Numerous collations of MSS., more or less perfect, have been made. In this, as in many other points, Bentley pointed out the true path which others have followed. His own collation of Latin MSS. was extensive and important (comp. Ellis, Bentleii Critica Sacra, xxxv. ff.). 49 Griesbach added new collations, and arranged those which others had made. Lachmann printed the Latin text in his larger edition, having collated the Codex Fuldensis for the purpose. Tischendorf has labored among Latin MSS. only with less zeal than among Greek. And Tregelles has given in his edition of the N. T. the text of Cod. Amiatinus from his own collation with the variations of the Clementine edition. But in all these cases the study of the Latin was merely ancillary to that of the Greek text. Probably from the great antiquity and purity of the Codd. Amiatinus and Fuldensis, there is comparatively little scope for criticism in the revision of Jerome’s Version; but it could not be an unprofitable work to examine more in detail than has yet been done the several phases through which it has passed, and the causes which led to its gradual corruption. (A full account of the editions of the Vulgate is given by Masch [Le Long], Bibliotheca Sacra, 1778-90. Copies of the Sixtine and Clementine editions are in the library of the British Museum.)

VI. The Materials for the Revision of Jerome’s Text. — 30. Very few Latin MSS. of the O. T. have been collated with critical accuracy. The Pentateuch of Vercellone (Romæ, 1860) is the first attempt to collect and arrange the materials for determining the Hieronymian text in a manner at all corresponding with the importance of the subject. Even in the N. T. the criticism of the Vulgate text has always been made subsidiary to that of the Greek, and most of the MSS. quoted have only been examined cursorily. In the following list of MSS., which is necessarily very imperfect, the notation of Vercellone (from whom most of the details, as to the MSS. which he has examined, are derived) has been followed as far as possible; but it is much to be regretted that he marks the readings of MSS. Correctoria and editions in the same manner.

(i.) MSS. of Old Test. and Apocrypha.